LETTERS FROM THE GLOBAL PROVINCE

Keeping Your Head, While Others Are Losing Theirs, Global Province Letter, 19 September 2012

Let me introduce myself first: the Happiness of Being Well, at your service. I am not the prettiest, but I am the most important. …This is the Happiness of Pure Air, who is almost transparent…. Here is the Happiness of Loving one's Parents, who is clad in grey and always a little sad, because no one ever looks at him…. Here are the Happiness of the Blue Sky, who, of course, is dressed in blue, and the Happiness of the Forest, who, also of course, is clad in green: you will see him every time you go to the window------- Belgian poet, dramatist and essayist Maurice Maeterlinck

Keeping Your Head. There's an old shipboard saying, "If you can keep your head, while all about you, others are losing theirs, then you're out of your bloomin' mind." People have plenty to be crazy about. War, and poverty, and starvation, and strange illnesses (e.g., West Nile virus anybody?), and massive dysfunction are rife in most any nation. The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse are riding high. Irrationality has us by the throat. Cool men and women are in rare supply. Never in our lifetimes have they been so needed.

Nostrums. From the earliest times man has devised ways to achieve equanimity amidst a roller coaster world. The Stoics taught us to retreat into the mind, somewhat equivalent to the use of meditation in the Eastern religions. A protected garden surrounding a house of domestic pleasures, a sublime oasis, was the answer of the Epicureans to a fractious society.

We ourselves are most charmed by those who suggest we remake our present to be more like the past. In Building a Bridge to the 18th Century: How the Past Can Improve Our Future, the marvelous essayist Neil Postman says we could do worse than to imprint our country and our universe with the values running through the West in the 18th. This would offer society at large, rather than just an elect few, the joys of a thoughtful and communitarian nation. A blog, View from Here, even instructs us on how to surround ourselves with 18th century domestic bliss.

Montaigne, the great French essayist, constructed a "Solarium" in which he wrote the bulk of his essays. It is arguable that he thought he had to pull away from his fellow man in order to see and think clearly. As understood by Steve King, he thought this went hand in hand with the mental detachment by which one could lead a worthy life:

In "On Controlling One's Will," one of the last essays in his final collection, he proudly agrees with his detractors: "They also say that my term of office passed without leaving any trace or mark. That is good!" He goes on to recommend such detachment to all:

He who does not gape after the favor of Princes, as after a thing he cannot do without, is not greatly piqued by the coolness of their reception and countenance, nor by the inconstancy of their affections. He who does not brood over his children or his honors with slavish fondness, will manage to live comfortably after he has lost them.

In other words, there are those who pull away from society, in one way or another, to escape the pain and disturbance of reality. For Montaigne, however, a drawing back was not for escape, but in order, godlike, to view earth and its inhabitants more clearly. Which makes him a worthy model for us in these tremulous times.

Beating Back Digitalis. For those of us who would seek equanimity, there is a further reason for creating a Solarium for ourselves. For 24/7 (all day and night) a great mass of individuals in all the developed and even semi-developed nations are pelted by digital information through their cell phones, and iPods, and iPads, and TVs, and radios, and ATMs, and so on. We are analog people trying to adapt to digital germs. The artificial world to which many are condemned spews bits, pieces, events, even though our brains and consciousness are constructed to ingest a continuum. America's most interesting philosopher, William James, talked of a "stream of consciousness" where all consciousness was irretrievably linked. Like atomic fission, our digital devices have smashed our consciousness and fragmented our lives. We rarely talk about the disquieting effects of such a digital onslaught though some occasionally admit that 8 hours of computer games may not be doing nice things to our children.

Arguably we must take long sabbaticals away from the digital cocoon if we are to successfully deal with a world that does not really exist in a screen. We cannot see things clearly if we are locked into a very small part of it.

Bursting Out of Our Cells. We have argued that we have to see the world in a different way if we are to have equanimity. Perhaps we need to bleed more of the arts into our daily regimen. The University of Chicago, which we have always thought of as a somewhat gloomy university, is lightening up by bringing the creation of art into the daily lives of its inhabitants. Says the Wall Street Journal, "Several of our great universities are beginning to rethink their aloof attitude toward the making of art, but the University of Chicago may be ahead of the game. It has recently spent millions of dollars on recruiting top artists for its faculty and on a bricks-and-mortar project to support the integration of art into the curriculum."

"Mr. Zimmer is a mathematician whose specialties, according to his university biography, are "ergodic theory, Lie groups, and differential geometry." But nurturing the arts has been one of his priorities. "We started talking about the arts as an opportunity for the university within the first few months after I left Brown as provost and came back here as president," he said to me in his office. "We have a great research university sitting in the middle of a great city. Arts are a natural place where a university can contribute to and benefit from the city.""

Zimmer is spending a lot, and we don't know whether he will get it right. But, in theory, the way to truly broaden the vision of students, and professors, and the whole society at large is to help people view their world more creatively so that they don't accept the daily dross that is inflicted upon them. The way to deal with a world that has turned volatile and disturbing is to summon up creativity that sees things as they are and then reworks the whole. At least Zimmer is on to something in using art to take people out of their silos.

Of course, the university with the deepest tradition of mixing art into its course offerings is Yale. First of off, Yale students live on the most spectacular campus architecturally in the United States, the fruit of the presidency of A. Whitney Griswold. But Yale's closeness to the arts dates back to 1869 when John Ferguson Weir became the founding dean of Yale's new art school.

Weir was an accomplished painter, putting a visual stamp not only on the art school but on Yale itself:

Also like his father, Weir became a painter. (A brother, J. Alden, became a leading American Impressionist.) In 1864, his first exhibited painting—a view of his father's studio—led to Weir's election as an associate of the National Academy of Design. He exhibited his next work, The Gun Foundry, in 1866 to great critical praise. After selling the picture for $5,000, Weir married Mary French, the West Point chaplain's daughter. In 1868 he completed his third great painting, Forging the Shaft. (Fire destroyed the original in 1869, but Weir's reproduction now hangs in the Metropolitan Museum.)

His statuary is also seen about in New Haven.

Difficult times, where today seems to bear no relation to yesterday, require vastly different imaginations than the placid days of yore when it made sense for tomorrow to be a great deal like yesterday. It's a different sort of mind, a creative mind, that can be at ease in a world that seems to be out of control. Others lose their minds amidst the tumult.

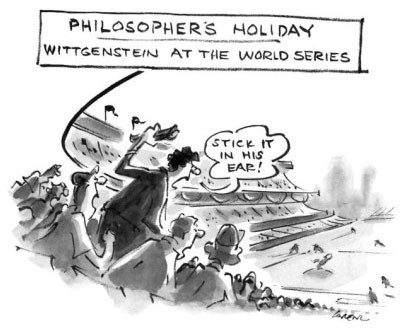

Philosopher's Holiday. Irwin Edman, a New Yorker and very accessible philosopher, wrote Philosopher's Holiday, a wonderfully written intellectual memoir, in 1938. The nation was still mired in Depression, and some could see a great war on the horizon, with unpleasant little wars already afoot in both Spain and China. Certainly there are similarities between that year and our present circumstance. Edman's last chapter, "The Bomb and the Ivory Tower," travels between the joys of life and the trials of 1938. He can keep his head because he embraces art and philosophy, even while facing up to the horrors of his age.

"Life becomes, even in a troubled and anxious period, for brief times, a joy merely to participate in, in love or friendship; to behold, in art; or, less often, a joy, tinctured with sadness, to understand. But in a society where the bombs batter against the mood of felicity, art and philosophy must, for the most part, be moral holidays."

It is the task of good men in our own age to deal with the deprivations and depravity that are about, while remembering that humanity lurks somewhere in the background. Above all, we require leaders who have such a creative point of view, using equanimity to push back chaos. For very practical reasons we're in search of people who not only can see far ahead, but can also cast their eyes left and right to capture a rounded view of affairs.

Home - About This Site - Contact Us

Copyright 2012 GlobalProvince.com