LETTERS FROM THE GLOBAL PROVINCE

Much Ado About Nothing: Brain Tales, Global Province Letter, 12 August, 2015

No Story There. In the course of our doctoral work, we did a paper for the great German war historian Sir John Wheeler-Bennett. Quite a dashing fellow, good looking, tall, robust but not fat, with a great shock of hair, he was a hail fellow well met on any occasion. He loomed large and got about with a walking stick. His colleagues seemed diminutive and a bit shoddy beside him. Often he might be wrapped in a tweedy jacket.

Our paper looked at what the German academics did during the Nazi period. Sir John could not praise the paper enough. "You did a first rate job. And you discovered there was nothing there." Indeed the German academic community had been rather supine in the face of Hitler's tyranny. If any of that tribe whistled, nary a sound was heard.

Sir John was never supine: luckily for him since he obviously worked for the British Government while in Germany, he had moles who told him what was going on. He left Germany on the night train on The Night of the Long Knives, a few steps ahead of Hitler's murderous mini.

Summer Reading.

We were reminded of Wheeler-Bennett when we read two rather new books this summer. Henry Marsh in Do No Harm: Stories of Life, Death, and Brain Surgery

not only demonstrates why he is an English cancer surgeon of the first rank but is a morally interesting man besides. He is bluntly honest with himself and with us readers about the fact that he loses a goodly percentage of all the people he operates on, that he often tells white lies to patients in order to give them some hope as they go into the operating theater, and that overall he is in a daunting occupation that would fill any man with despair no matter how detached. He does not drape himself in glory. It is somehow pleasing to know that he bikes to the hospital from his nearby home.

A bit more vain and certainly a great deal more troubled is Oliver Sacks, an Englishman turned American, who gives an account of his life and career just in time, as it turns out, because he has terminal liver cancer. On the Move: A Life

is as much a revelation of his mental and physical difficulties in life as it is about his chosen field of study—brain diseases. For those of us who feel that he is a charming man who writes terribly well about this and that oddity, the longish, revealing book is as well a shock since we learn he was once a passionate bike (motorcycle) rider who swept across America to escape the confines of his mind and occupation. His research is heavily descriptive of some of the brain's strange diseases and complaints, but does not offer much in the way of solutions.

Both these wonderful books remind us that brain study is the last frontier of medicine, and all the scrutiny about the stuff going on in our heads is in a very early stage. Both these doctors are wonderful at narrative, putting them much in tune with the drift towards narrative medicine in the present day. Except, of course, with the brain there is yet no story, only the beginnings.

A Rash of Doctors Writing. Marsh and Sacks are only two out of a whole corps of doctors who write with wit and illumination about sundry aspects of healthcare. Prolific, for instance, are Atul Gawande and Jerome Groopman, Harvard types who write for the New Yorker about outrageous healthcare costs, flawed practices and how to remedy them, excessive, costly medical procedures, etc. In fact, medical journalism is the secret weapon of the New Yorker, the magazine having declined in other departments. We ourselves have learned about medical tidbits in its pages that we have been able to recommend to the afflicted around the United States. For those who want to learn about "Doctors Who Wield the Pen to Heal the Profession," one should read Ms. Abigail Zuger M.D. in the New York Times in May 2007. She, of course, barely scratches the surface. For instance, one has to take a look at Richard Selzer, onetime professor of surgery and teacher of writing at Yale University, who shined well before Dr. Zuger started her heavy reading.

What should we make of the exponential rise in healthcare reporting and doctor-led medical journalism? In some way it is a huge negative. It points to the fact that the healthcare sector of our economy has grown too large (as has the financial services sector) and is draining capital away from things that keep the economy humming and which put meat on the dinner table. Healthcare has become an economic parasite.

With the aging of our population, there has been an epidemic growth in chronic disease, the afflictions that last year after year after year and never quite go away. We see so much about health and disease because affliction has gotten woven into the fabric of America. We read so much about it because it is too much on our minds.

But we really must welcome the rise of well-written, thoughtful, not quacky articles in print. We are not making quantum leaps in medicine, all the blather to the contrary. These writings often wipe away the obfuscation that permeates the medical community. Medicine is not today offering great solutions or great advances in treatment. It is much too much controlled by big institutions, insurance companies, government agencies, and play-it-safe academic factories. The medical establishment cannot and will not produce great Mount-Everest- type victories such as pasteurization, anesthesia, or penicillin. The big and new will have to come from outside our expensive, self-perpetuating medical officialdom.

A thoughtful and free-thinking medical press will cause good things to bubble up elsewhere. Sea changes in everyday medicine will not come from Boston; Vienna is unlikely to produce earth shattering developments in mental health. There convention rules. Just as offbeat guys who could read the medical columns welled up from Australia and finally announced what ulcers were all about, other breakthroughs will come out of the bush. The Aussies incidentally have done some interesting things, counter to received theory, in the area of Alzheimer's. Big things will come from small places at the edge of the map.

Apologia Pro Vita Sua. Marsh and Sacks, both fine and productive men of much more than average character, do a great deal of apologizing for their failures and for not doing more about the diseases of men. Whatever their deeds of good and skill, they both seem to know that their efforts only amount to a drop in the bucket in men's battle with mortality and its hurts. It's nice that they both seem to have pretty large egos, but that warm streams of humility also course through their bodies.

Isn't it ironic that such as they can apologize, but that the abundant supply of men who are less than men never can utter a peep of regret?

P.S. Most of the big gains in health for the foreseeable future will come not from one-on-one treatments of individuals but from far reaching public health measures that deal with the contaminations of our unhealthy society. It's not just cigarettes, but the medley of chemicals which pour into our pores, from plastics and other noxious artifacts in our environment. That is beyond the ken of ordinary physicians.

P.P.S. Finally we are making a bit of headway on the obesity epidemic and the rash of diseases resulting from too much food and, as importantly, too much ingestion of thoroughly bad foods. There is broad evidence that Americans are getting some control of their diets. In particular they are drifting away from canned soda, with consumption down 25% or so. The exponential rise in obesity can be best dated to the shift to fructose away from sugar in soft drinks, since it sticks like glue to the body. Coca Cola, unfortunately, is trying to convince Americans that soda is not such a culprit, pushing exercise as a weight cure instead.

P.P.P.S. We have long thought that the sick themselves often generate some of the most interesting cures for their own afflictions. In "Short Cuts" this week, we discuss two ways to get at pain no doctor would dream up, but which suddenly occurred to those who were hurting. More than a few people who thought they were going to die have retired to Ikaria in Greece for their final days, but then find a new lease on life in these life giving islands. Doctors who have suffered from a disease often do quite a bit more than most to cure it: Dr. Andrew von Eschenbach, whose father died of prostate cancer, and who had a bout with it himself, has broadly pushed deep research into its causes and cures.

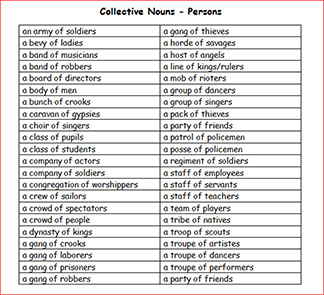

P.P.P.P.S. We are forwarding "rash of doctors" to several of our wordsmith friends in hopes that this might get added to some dictionary of collective nouns. It is much better than a "confab of doctors." For more on such nouns, read about collective terms.

P.P.P.P.P.S. It is a great garden year and a time to make very, very fresh jams. Fig, for instance.

Home - About This Site - Contact Us

Copyright 2015 GlobalProvince.com