LETTERS FROM THE GLOBAL PROVINCE

What Do Customers Want, Global Province Letter, 23 April 2014

Harvard Business Review. Somewhere in the very distant past the Harvard Business Review was a vital mouthpiece for a storied business school that helped point businesses toward greater sales, profits, and economic relevancy. According to Wikipedia, “Following World War II, HBR emphasized the cutting-edge management techniques that were developed in large corporations, like General Motors, during that time period. Over the next three decades, the magazine continued to refine its focus on general management issues that affect business leaders, billing itself as the "magazine for decision makers." Prominent articles published during this period include, "Marketing Myopia" by Theodore Levitt and "Barriers and Gateways to Communication" by Carl R. Rogers and Fritz J. Roethlisberger.”

Harvard Business Review. Somewhere in the very distant past the Harvard Business Review was a vital mouthpiece for a storied business school that helped point businesses toward greater sales, profits, and economic relevancy. According to Wikipedia, “Following World War II, HBR emphasized the cutting-edge management techniques that were developed in large corporations, like General Motors, during that time period. Over the next three decades, the magazine continued to refine its focus on general management issues that affect business leaders, billing itself as the "magazine for decision makers." Prominent articles published during this period include, "Marketing Myopia" by Theodore Levitt and "Barriers and Gateways to Communication" by Carl R. Rogers and Fritz J. Roethlisberger.”

But somewhere around 2000 it stagnated editorially, losing intellectual crispness and strategic orientation, such that it particularly foundered in the United States, though it did seem to hold onto its international franchise. In part of course it merely shared in the general decline of print media that has decimated our newspapers and closed the doors of so many magazines. Time, the former home of the current chieftain of editorial operations for the whole HBR Group, is a mere shell of its former self, looking like it has been attacked by some rare, incurable cancer. As well, however, both the magazine and the whole group seem to have lost the umbilical cord that tied it to the core of American business. Instead it seems to be an outlet for the musings of business consultants who themselves are divorced from the economy they seek to explain.

In Touch With Out of Touch. If the HBR Group (and, by implication, maybe the Harvard Business School) has lost its connection with the markets it seeks to explain, it is ironic we think that it has done such a good job of profiling how often companies misunderstand their customers and fail to provide the products and services they need.

Way back in March 1966, it ran a seminal article by Warren J. Wittreich on “How to Buy/Sell Professional Services” which offers a slew of trenchant insights. Key is one idea. Wittreich argues that in professional engagements neither buyer nor seller really know what is wanted. The whole contracting experience at its best is an iterative process where both try to get steadily more concrete as to what is being bought and sold. In truth, the deliverables continue to be redefined even when the engagement is begun as both discover that what was contracted for is only an approximation of what really must be done. This article, by the way, is so important and so influential that all the consultants who have written about professional services steal from it in their own writings, often without bothering to credit Wittreich.

Way back in March 1966, it ran a seminal article by Warren J. Wittreich on “How to Buy/Sell Professional Services” which offers a slew of trenchant insights. Key is one idea. Wittreich argues that in professional engagements neither buyer nor seller really know what is wanted. The whole contracting experience at its best is an iterative process where both try to get steadily more concrete as to what is being bought and sold. In truth, the deliverables continue to be redefined even when the engagement is begun as both discover that what was contracted for is only an approximation of what really must be done. This article, by the way, is so important and so influential that all the consultants who have written about professional services steal from it in their own writings, often without bothering to credit Wittreich.

Companies We Hate. But the gap between customer and provider does not just occur in the rather intangible world of professional services. Big industries, such as banking, cellphone service providers, and and credit cards, trot out product and service packages that fall wide of the mark—with features that fit the convenience or easy-profit desires of the provider, but have little to do with the customer. We have previously essayed on this in “Companies You Love to Hate.”

Once again, HBR hit this problem right on the head. Gail McGovern and Youngme Moon talk about the foolish and wasteful ways of such companies in “Companies and the Customers Who Hate Them.”:

The Slippery Slope

Companies can profit from customers’ confusion, ignorance,

and poor decision making in two related ways. The first

evolves out of the legitimate attempt to create value by giving

customers a broad set of offerings. The second emerges

from the equally legitimate decision to use fees and penalties

to cover costs and discourage undesirable customer

behavior.In the first case, a company creates a diverse product and

pricing portfolio to offer various value propositions to different

customer segments. All else being equal, a hotel that has

three types of rooms at three price points can serve a wider

customer base than a hotel that has just one type of room

at one price. However, customers benefit from such diversity

only when they are guided toward the offering that best

suits their needs. A company is less likely to help customers

make good choices if it knows that it can generate more

profits when they make poor ones.Of course, only the most flagrant companies would explicitly

seduce customers into making bad choices. Yet there are

subtle ways in which even generally well-intentioned firms

use complex portfolios to encourage suboptimal choices –

tactics that hasten the descent down the slippery slope. Complicated

offerings can confuse customers with a lack of transparency

(hotels, for example, often don’t reveal information

about discounts and upgrades); they can make it hard

for customers to distinguish among products, even when

complete information is available (as is often the case with

banking services); and they can take advantage of consumers’

difficulty in predicting their needs (for instance, how many

cell phone minutes they’ll use each month).Companies can also profit from customers’ bad decisions

by overrelying on penalties and fees. Such charges may have

been conceived as a way to deter undesirable customer behavior

and offset the costs that businesses incur as a result of

that behavior. Penalties for bouncing a check, for example,

were originally designed to discourage banking customers

from spending more than they had and to recoup administrative

costs. The practice was thus fair to company and

customer alike. But many firms have discovered just how

profitable penalties can be; as a result, they have an incentive

to encourage their customers to incur them – or, at least,

not to discourage them from doing so. Many credit card

issuers, for example, choose not to deny a transaction that

would put the cardholder over his or her credit limit; it’s

more profit table to let the customer overspend and then impose

penalties.

The authors contrast large well-known companies with tricky offerings wit the very virtuous few that are simple and straightforward, companies which as a result have low customer churn and much lower marketing costs.

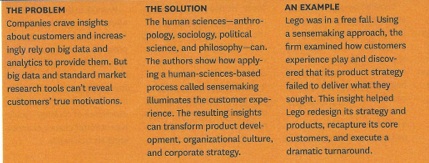

Going Beyond Big Data. In the present age, our marketing mavens, equipped with the data crunching power of their wondrous computers, believe they can gather enough data to tell us what markets and consumers need. But flagging sales in several companies and numerous markets tell us that all their data does not capture the vital truth. This has always been a problem in market research. We collect mountains of facts and expect them to explain to us the secrets of consumer behavior and market potential. But it is not that simple. A keen observer ultimately must visit the stores and bars and restaurants where the customers are in order to make sense of the data in a way that leads to the right products and services. This is what we discover in spades in “An Anthropologist Walks into A Bar…”

Flat Markets. There is ample evidence that many, many companies are producing products and services customers neither need nor want. In part this results from incompetence. In part it results from the fact that it is no easy task to find out what people want, and their wants are ever evolving. And, we discover, it also results from the cynical offerings of large institutions who have a lot of marketplace power and feel that they can force the customer to buy defective, bulbous products.

In any event we now find that many, many markets are hardly growing or growing not at all in these United States. A lot of sectors have not achieved real growth for several years, depending on increasing their apparent volumes through price hikes and other devices. Ultimately however real growth will depend on devising genuinely needed products that meet the market.

P.S. All the rage now is French economist Thomas Piketty whose Capital in the Twenty-First Century is creating quite a storm. He argues that income equality is worsening and will continue to do so, with the gains in the economy going to those with lots of capital, rather than to wage earners. To some degree, he is missing an even bigger point. Current dysfunctionalities in capitalism have produced tepid economic growth and moribund companies that are neither serving customers or the economy. Capitalism at the moment is not being very capitalistic, suffering from the same gridlock as government. In the private sector there is a flagrant misappropriation of capital with financial service companies and other middlemen enterprises siphoning off resources that should be going into more useful and less parasitic enterprise.

Home - About This Site - Contact Us

Copyright 2014 GlobalProvince.com