LETTERS FROM THE GLOBAL PROVINCE

Randy Tortoises, Yellow-Eared Parrots, Iran in Mississippi, Thirty Dollar Cellphones, Global Province Letter, 1 August 2012

In Classical times it was not the Tortoise's plucky conduct in taking on a bully that was emphasised but the Hare's foolish over-confidence. He really is the faster, but should not have assumed he could win the race without trying. ---About The Tortoise and the Hare.

The Lure of the Galapagos. Thirty years ago we came across a monstrously prolific freelance writer in New York City named Bill Hunter who could churn out articles at a mad clip. If the newspapers today could only hire the like of him, they would slice their payrolls in half. He had been everywhere, but we think he delighted most in his visit to the Galapagos Islands. From one short trip he was able to conjure up six articles, but he shrewdly understood that the demand for his wordsmithing did not stem from the brilliance of his writing but from Western man's enduring fascination with the Galapagos.

There are spots on earth –Timbuktu, Everest, the Galapagos---that are magic vortices, which draw men into their embrace, even if these remotenesses are not tricked out with all the media-driven artifice of the world's great cities. The most mysterious spots on earth radiate unseen power because they do not reek of man. Even though the Galapagos is over-run with tourists and sundry naturalists, it retains the elusive glimmer of other-worldliness.

Elizabeth Hennessy, an associate of our firm and, more importantly, a doctoral candidate in geography at the University of North Carolina, has long felt the magnetic pull of the islands where Darwin harvested so much knowledge. Here she gives an account of her many visits. She went, as she tells us below, even though she had never envisioned going there. What emerges is that it is in distant corners such as this, well off the map of the developed world, where we nakedly encounter the epic battle to defy devastation, to save the earth and its species, both of which have been terribly taxed by the predations of men so caught up in their daily activities that they can have no thought to the future of the planet that sustains them. As well, we may sense that several of the more interesting conversations on earth may be happening outside our hearing in such hard-to-reach regions that are not connected to the world's daily dialogue:

The Galápagos Islands are one of the world's most storied tropical archipelagos, famous for their unusual species, inspiring Darwin's theory of evolution, and more recently, as a top eco-tourism destination. A trip to the Galápagos Islands is a dream for many people. It was never one of mine. But the place is full of charismatic creatures; it is hard not to be amazed. Galápagos is a place where you can see a giant tortoise that might just have been alive when Darwin was there. Where piles of monstrous black marine iguanas are enough to give you nightmares, but where Darwin's famous finches will perch on your laptop, and friendly sea lions will give you a belly roll as you swim by.

Since 2007, I've made 5 trips to the islands and this past year I spent 5 months living there—all for my dissertation research on the challenges of conservation and development. Galápagos may not be where I thought I would do research, but it sure beats a cold, sterile laboratory and stuffy library stacks. My research focuses on the islands' most iconic species, the giant tortoises, which sit at the nexus of tensions between conservation and development. As you might expect, researching tortoises is slow going at times, but during the course of my work I have tracked tortoises up long-dormant volcanoes; measured, fed, and cleaned up after captive tortoises; helped to take blood samples; and excavated eggs from nests to be incubated at the conservation breeding center. Of course, I have also interviewed a lot of people about these animals—scientists, conservationists, tourists, and local residents all have something to say about this famous species. Drawing on this experience, here I tell the tale of two of the islands' most famous tortoises, George and Diego.

A Tale of Two Tortoises

George and Diego each live in corrals at the Galápagos National Park's headquarters, where guides shepherd tourists through thick green vegetation along rocky paths and a wooden boardwalk to see the islands' namesake animals. The giant tortoises that live in these corrals—80-some adults—are part of the islands' signature conservation program, focused on captive breeding and repatriating these endangered species to their native island populations. George and Diego, or more specifically, their sex lives, are at opposite poles of this nature protection program—they are a reptilian odd couple representing the fears and dreams of Galápagos conservationists. George is famous for being "lonesome"—the last of his particular species of giant tortoise, from Pinta Island—an animal whose atavistic existence spoke of histories of exploitation and human extirpation of this endangered species. His passing at the end of June was mourned in media reports across the globe and only underscored this fame. At the other end of the spectrum, Diego, not yet as famous, is doing his best to ensure that his species does not meet the same fate. Far from lonesome, "Macho" Diego is the star stud of the Park's breeding program; he has helped to send more than 2,000 baby tortoises back to his home, Española Island, over the past 40 years.

I got to know George and Diego, as well as the other adult and baby tortoises that live at the park headquarters last fall, while I volunteered at the Giant Tortoise Breeding Center. For a month, I, along with two Park wardens and a couple other volunteers, fed the tortoises giant salads, swept up after them, and scrubbed their watering pools on hands and knees. The experience not only exposed me to the ins and outs of giant reptile gastronomy, but also gave me a first-hand look into the National Park's work on preserving nature.

In the midst of what scientists have called the third great age of extinctions, conservationists around the world are working fervently to prevent further loss of biodiversity. In the Galápagos, Park wardens and scientists have done their best to protect the archipelago's unusual endemic species—the giant tortoises, flightless cormorants, marine iguanas, and penguins found nowhere else in the world. But here, the goal is not just to protect this relatively "pristine" archipelago—Galápagos is said to retain nearly 95 percent of its "original" biodiversity—but also to restore nature to a past state. Going "Back to Eden," as one policy tome put it, is the ultimate dream of conservation in these fabled islands. This is, after all, said to be the place where Darwin "discovered" evolution—the "origin," he once wrote, "of all my views." As many nature documentaries would show you, Galápagos is no ordinary national park, but a "natural laboratory of evolution" where "prehistoric" goliaths like the giant tortoises somehow still roam the volcanic shores.When I set out to do my dissertation research on conservation in the Galápagos, I never thought I would end up writing about the sex lives of giant reptiles. But here I am. Perhaps I should have seen it coming—Darwin did show us that reproduction is the basis of evolution. Whether a species will thrive, diverge into new species, or die out ultimately comes down to whether its individual animals are environmentally fit enough to reproduce. At a moment when so much scientific and popular effort is funneled into saving our world's wildlife, the sex lives of iconic animals like George and Diego provide an illustrative lens into the possibilities—and impossibilities—of "saving" nature.

Restoring the "Tortoise Dynasty"

Giant tortoises have long been the most striking residents of the Galápagos Islands. Early sailors reported that the islands' shores were littered with these giants, which can reach more than 500 pounds and 4ft in length. The islands are even named for the tortoises—"galapago" is an old Spanish word for saddle. But while the tortoises never made for good steeds (Darwin recounted repeatedly slipping off their shells), they did make for a good meal. Before George and Diego were popular icons of conservation and tourism, the Galápagos archipelago was most often frequented by whalers and buccaneers who for centuries relied on the giant tortoises for fresh meat on long oceanic voyages. Based on ships' logs and sailors' journals, historians estimate that more than 200,000 giant tortoises were taken from Galápagos before conservation efforts began in earnest in the late the 1950s. Today, some 20,000 are thought to remain, scattered in populations across the volcanoes of this remote archipelago. Only 10 of what were once 15 different species of Galápagos giant tortoises now remain. Since the mid-1960s, conservationists have worked to "restore the tortoise dynasty" through what has become one of the most successful captive breeding and reintroduction programs in the world. Since the first reintroduction of baby tortoises to Pinzon Island in 1971, more than 4,000 captive-bred tortoises have been "repatriated" to different populations across the archipelago.

Diego is the single tortoise who has most contributed to this success, siring 40 to 45 percent of the nearly 1,800 juveniles that have been returned to Española Island. When conservation efforts began, the fate of the Española tortoises did not look much brighter than George's—Park wardens found only 14 tortoises (2 males, 12 females) on the island during several years of searching. All of them were brought to the Park's headquarters to breed under careful watch because conservationists were concerned that the few animals were so spread out on Española that they simply would not find each other. In 1978, following a call to zoos and other collectors to return tortoises to Galápagos to breed, a third Española male was flown down from the San Diego Zoo. When he arrived, Diego's aggressive behavior was a boon to the breeding program. He initially shared a corral with one other male and several females, but pushed the smaller male around so much that he was eventually left alone with his own harem of five females.

Each year, female tortoises generally lay two or three clutches of 6-10 eggs, all of which are quickly excavated by Park staff, carefully labeled, and nestled in incubators, where the next generation of giants is baked for the next 3 to 4 months. The sex of giant tortoises, like that of many reptiles, is dependent on the temperature at which eggs are incubated. Park wardens have a recipe for the baby giants—two-thirds of the eggs from each clutch are put in an incubator set at 29.5 degrees Celsius to produce females and one-third are incubated at 28 degrees Celsius to produce males. The ratio is designed to speed population growth. After they hatch, the babies spend the first four years of their lives at the Breeding Center, until they are big enough to be repatriated to their native islands. Over the past 40 years, nearly 1,800 juveniles have been returned to Española, where the population living in situ has reached almost 2,000, which scientists estimate is about the small island's carrying capacity. Even better, the early repatriots, now grown, have begun to reproduce in situ—the ultimate mark of success for a captive breeding and return program.

The Lonesomeist Tortoise

But if Diego's virility and the success of the Española program demonstrate the possibilities of conservation, then Lonesome George reminds us of the limits of human intervention in nature. Just a few feet away from all of this reproductive activity, George stubbornly and doggedly refused to participate in human dreams of a restored Pinta dynasty. But it wasn't for lack of trying.

George is often said to be an icon of conservation, an animal whose plight sounds a clarion call about species extinctions. With that fame has come a host of attempts to try to save his species. During my research, I spent two days hanging out on the platform that overlooks George's corral to try to understand this fame, interviewing passing tourists and listening to the stories their tour guides told. I asked tourists what they thought George's existence meant. In return, they just asked me where he was: Rather lazy in his last few years, George spent much of the hot season resting in a shady corner of his corral, just out of easy reach for tourists' cameras.

George was always a loner. When he was first brought to the Park headquarters after being found on Pinta in 1972, he was resolutely anti-social and would flee from human visitors as fast as his stubby tortoise legs would take him. The conservation community searched for a mate for George, first on repeated trips to Pinta, and then in zoos around the world. In the early 1990s, scientists gave up on hopes of finding a Pinta female and decided to try to get George to mate with females from a nearby population. The tourists delighted in stories of tortoise match-making. As the guides explained, the Park brought two females tortoises from Wolf Volcano on the Northern tip of Isabela Island to join George in his corral. Sparks did not fly. George largely ignored them. Just why George remained lonesome was an even more popular topic with the tourists. Guides told them of all the local speculation: Maybe George needed to be socialized after growing up alone on Pinta. Maybe he needed competition. At one point, Diego was put nearby in the hope that his virility would set an example, get George's testosterone going.

Maybe, some said, George was gay. Or impotent. A favorite George story is about a Swiss biology student who came to Galápagos to volunteer for a summer. Her assignment: get a sperm sample from George. She spent 3 months gaining George's trust, a task for which she would cover herself in tortoise pheromones, getting closer and closer until he would allow her to touch him. But she found no success. In 2008, the world held its breath when, after 20 years together, the females with George laid two clutches of eggs. Sadly, none were fertile. Just a year ago, the Park switched the two females with George to two from Española Island, shown to be the closest match genetically. Still, George was not interested.

And then on a Sunday morning at the end of June this year, his longtime keeper Fausto Llerena found George dead in his corral. Thought to be about 100 years old, this stubborn, chubby tortoise apparently died of old age, still lonesome and without an heir.

The contrast between these two tortoises' sex lives is a telling glimpse into the possibilities and limitations of conservation work. Diego can be said to demonstrate the promise of long-term dedication to helping along the continued reproduction of endangered species. On the other hand, George, as the tourists told me, demonstrates the plight of many species around the world—species that often cannot rely on the charisma of being a giant turtle or the fame associated with scientific origin stories and tropical island tourism.

George's story is also important, I think, as a frustrating reminder that despite decades of effort, and even with the best of intentions and resources, we cannot go back to a "pristine" past to amend for our own species' sins. As Darwin taught us, evolution is ever forward moving. Somewhat ironically, the fate of Pinta Island may now rest on Diego's shell. Even before George died, conservationists began discussing the idea of "re-tortoising" George's home island with babies from the Española breeders, since they are genetically closely related. Returning large herbivores to Pinta would potentially serve to balance the island's ecosystem. And maybe 100,000 years from now a new "Pinta species" will have evolved—not a return to Eden, but a new vision of hope that future generations will continue to be amazed by this place.

As enchanting, but much less well known, is the story of the yellow-eared parrots of Columbia, once even assumed to be extinct. "Endemic to these high, cloud-forested flanks of the northern Andes, the yellow-eared parrot is the sole species of a single genus, and dependent on its survival in Columbia on this one species of endemic wax palm, Ceroxylon quindiense. The parrot will nest in no other tree here. In the absence of quindio palms with commodious cavities, they forgo nesting. They die out." (See Audubon, March-April 2012, p.92). The problem then has been to entreat and entice the locals not to cut down the palms. Fortunately Columbian scientists have arrived at a modus vivendi with indigenous folks, and the parrots survive.

Indeed, it is at the corners of the earth such as Ecuador or Columbia, often next to the world's poor, that the most interesting attempts to save species and preserve land cover occur, sociological conservation experiments that may provide lessons for developed nations which have been even more feckless in their uneasy duel with nature. The real task in conservation is to persuade local powers to conserve their natural riches.

Iranian Healthcare in Mississippi. In "Hope in the Wreckage," The New York Times Magazine, July 20, 2012, pp.22-29, we learn that Dr. Aaron Shirley and Professor Mohammed Shahbazi have undertaken an interesting public health experiment in Jackson, Mississippi which promises to improve the health of a devastatingly afflicted poor population and to lower costs. Basically, the approach consists of sending trained nurses and health practitioners out to visit and talk health at patient homes. Once a relationship is formed, the idea is to provide continuous coaching so that patients learn what to do and to identify possible resource support, all to keep them out of hospitals. "The Iranians built 'health houses' to minister to 1500 people who lived within at most an hour's walking distance." "Iranians have reduced rural infant mortality by 75 percent and lowered the birthrate."

It's interesting enough that a Third World nation should supply a model that might turn around healthcare in a Western country in which all other efforts at cost reduction and health improvement have been duds. We suspect that China, which now is bringing intense focus to healthcare, will soon have a lot of lessons to provide the West as well. Poor countries may teach survival skills to our poor, since our own society, no matter how well meaning, cannot get the job done.

It is instructive, as well, that genuine healthcare reform seems to bubble up in the most desperate of situations. When Finland started its own successful healthcare revolution, which has made dramatic inroads in cancer and heart disease, it launched its first efforts in its poorest province. In the United States, poor, beleaguered Camden, next door to Philadelphia, has made health gains by treating chronic patients with continuous health care rather than emergency room visits. This suggests that healthcare systems in affluent areas are generally at the heart of the problem, rather than at the core of the solution to our healthcare black hole.

$30 Cellphones and Microloans. As we have pointed out, many multinationals have learned that advanced markets in developed nations are mature and peaking out. They do not provide enough demand for big, growth companies. Smart companies such as Unilever, Nestle, GE, and GM have had to go to so-called poor countries to recharge their batteries.

But this has meant, as well, that they have to devise entirely new products suited to poor consumers, styled without all the excessive complexity and outrageous cost engineered in by Western product development teams. The result has been very lean products, indeed. The brightest companies are then carrying these products back to the West, as a way to re-engineer product lines that have grown fat and foolish.

This inventiveness has led to dynamism, not only in China and India, but also in other countries that are on the move. Indonesia, with an economy now expanding at 7% plus a year, has agile telecoms that sign up new cellphone subscribers for one dollar and equip them with 30-dollar cellphones. Microloans are booming there, even as big borrowers have trouble raising money.

As Robert Neuwirth points out in a "Slumdog Economist" interview, not only is much of this commerce taking place in the farthest flung nations of the world, but it is commonly hidden, often transpiring in an underground economy, away from all the big companies and their old-fashioned distribution networks. "Not many people think of shantytowns, illegal street vendors, and unlicensed roadside hawkers as major economic players. But according to journalist Robert Neuwirth, that's exactly what they've become. In his new book, Stealth of Nations: The Global Rise of the Informal Economy, Neuwirth points out that small, illegal, off-the-books businesses collectively account for trillions of dollars in commerce and employ fully half the world's workers. Further, he says, these enterprises are critical sources of entrepreneurialism, innovation, and self-reliance. And the globe's gray and black markets have grown during the international recession, adding jobs, increasing sales, and improving the lives of hundreds of millions. It's time, Neuwirth says, for the developed world to wake up to what those who are working in the shadows of globalization have to offer."

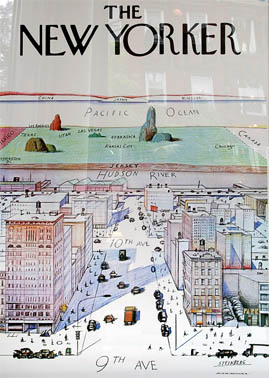

The New Map of the World. Even now, a good summer read is David McCullough's The Greater Journey: Americans in Paris which lingers on the 19th century visits of educated Americans to Paris, then felt to be the city where one made and remade oneself. Europe was still the center of one's phantasies and hinted at something better and superior to even the most chauvinistic of Americans.

There's a quaintness to all this. Even in the 20th century, one could still think that Paris was the center of something, just by giving a read to Harry's Bar: 1911-2011 where you learn how Americans abroad had to make obligatory stops at Harry's New York Bar (in Paris). But the world has moved on whether one is seeking riches, new geopolitical ideas, or nostrums to save the planet.

In our last letter, we included a disquisition from Fernando Henrique Cardoso, onetime president of Brazil, which more than makes clear that his country is now having its day in the sun and that it will soon be moving our planet in new directions. We have a deeper and deeper need to see the world in a new frame, which excludes Europe, and New York, and even China and Japan. The locus is shifting. The action is elsewhere. Indeed, South America has been a tortoise, long a sluggard amongst the world's continents, but now it is coming into its own.

P.S. Here is a Galapagos bibliography, which is a good starter kit for the uninitiated. http://www.galapagos.to/BOOKS.HTM.

P.P.S. One cannot contemplate tortoises without hearkening back to the joke about the snail and the sloth. In fact, we are going to put out a requisition to various jokemasters for a raft of tortoise jokes.

P.P.P.S. We've not had tortoise but a million moons ago we enjoyed fresh sea turtle in Bahia de los Angeles. We can imagine that tortoise is delectable, too. But, in the present day, we would have to forgo such pleasures.

P.P.P.P.S. Tip O'Neill used to say "All politics is local." Truth is, just about everything significant is local: things of substance happen in a little place somewhere at a specific time in a specific context. Maybe some place like Bunker Hill. The task for somebody who wants to get something done is to find the mother lode wherever it happens to be.

Home - About This Site - Contact Us

Copyright 2012 GlobalProvince.com