LETTERS FROM THE GLOBAL PROVINCE

What’s the Answer? What’s the Question? Global Province Letter, 8 June 2011

The Heisenberg uncertainty principle says that the more one knows about where a particle is right now, the less one knows about how fast it is going and the direction that it is going. This also works the other way around: the more one knows about how fast the particle is going and the direction it is going, the less one knows about where it is right now.—Wikipedia

The Destruction of Certainty. In some senses, the 20th century was the spectacular American moment when our country soared to the top of the pantheon of nations, allowing blue jeans to conquer the world. We became the greatest show on earth. But around the globe, it was as well the time when philosophy imploded and when, on the big questions, we no longer had answers, and no longer quite knew what we should be asking. Thinkers got tied up in knots triple parsing the meaning of language, agonizing over the limits of knowledge, and treating thought as a mathematical or logical exercise rather than as a journey into awareness.

The Destruction of Certainty. In some senses, the 20th century was the spectacular American moment when our country soared to the top of the pantheon of nations, allowing blue jeans to conquer the world. We became the greatest show on earth. But around the globe, it was as well the time when philosophy imploded and when, on the big questions, we no longer had answers, and no longer quite knew what we should be asking. Thinkers got tied up in knots triple parsing the meaning of language, agonizing over the limits of knowledge, and treating thought as a mathematical or logical exercise rather than as a journey into awareness.

Germany’s brilliant Werner Heisenberg gave us his Uncertainty (or Indeterminacy) Principle in 1927 and should rightfully be called the father of our unmooring. Some commentators like to claim that his theories only applied to the sub-atomic world of quantum physics and had no broad application to the wide world of knowledge. But it would seem that he cut the cord that bound us to the past, and sent the ideas of cause and effect and an understandable universe out to sea. Ever since, all truths have become relative and short-lived and peppered with a lot of ands, ifs, and buts. Academics in other fields, artists, political leaders, even theologians have become his sidekicks, centering our attention on the microscopic and claiming that the world of waves and particles defied human intuition. By the 1920s, we had travelled light years beyond the eighteenth century when a framer of our Declaration of Independence could “hold these truths to be self evident.”

Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going? Oft as not, the output of scientists and philosophers is late to the party, prefigured decades before by artists who are somehow in touch with the currents that are driving world affairs. In this regard, Paul Guaguin comes to mind whose beautiful Tahitian paintings circa 1897 suggest we are lost in the universe without a clue as to where we are or where we are going. The 20th century has stripped us of our mental foliage.

In fact, it is the artists who ask such shadowy questions who interest us in our present era. It is as if they know all too well that the world we thought we knew has been destroyed in the 20th. They are honest enough to be muddled. Their art is interesting because they fiddle with all sorts of media and channels of expression, not finding one that asks or answers the right questions.

David Byrne. For instance, there is David Byrne. He’s into music, and art, and writing, and opera, and god knows what else. In fact, his website is a mess, hard to navigate and understand. He is renowned as the creator of Talking Heads. We had always avoided him when possible and were a bit put off when we encountered his music or art which mostly seems like design to us. But, pure chance, we picked up Bicycle Diaries and found him to be a dazzlingly bright guy dwelling on the right grey areas of art and knowledge. We cannot recommend his writings enough. For instance, he ponders current perceptions of beauty:

Matthias says beauty, being ephemeral, evanesecent, and impermanent, reminds us of death. I would have never put an equal sign between the two myself—this statement seems overly romantic a la Rilke, but I see his point.

And Byrne cites Tibor Kalman, a somewhat interesting New York designer from Hungary, who apparently said, “I have no problem with beauty, but it isn’t interesting.” Beauty it seems is both elusive and maybe repugnant to the modern artist.

Steve Martin. Steve Martin is a comedian who wants to be taken seriously. So he has abandoned his crazy TV routines where he snickered, “Well, excuse me” and in which he whispered to us, “Let’s get small.” Now it’s movies, plays, banjo playing with Earl Scruggs, and such. He reminds us, who knows why, of the comic Ed Wynn with whom we accidentally dined about 50 years ago. For some reason he was in a raincoat: we cannot remember why. But he must have gotten splashed upon earlier in the afternoon. We expected ribald tales and other nonesuch, but the evening was pleasantly and insistently serious. He wanted us to know he thought about things.

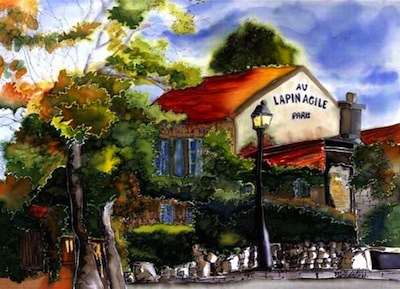

Martin, like Bryne, likes to ruminate a bit on the creative process. His Picasso at the Lapin Agile (at the Nimble Rabbit Bar with Einstein incidentally) suggests, “Focusing on Einstein’s Special Theory of Relativity and Picasso’s master painting, Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, the play attempts to explain, in a light-hearted way, the similarity of the creative process involved in great leaps of imagination in art and science.” We have not read the play and cannot tell you if Martin is onto anything. But it is interesting to see Martin—and Byrne—ponder how art gets created in the shadow of Heisenberg. Their elliptical notions, though provocative, explain perhaps why the 20th century did not produce artistic greatness.

Martin, like Bryne, likes to ruminate a bit on the creative process. His Picasso at the Lapin Agile (at the Nimble Rabbit Bar with Einstein incidentally) suggests, “Focusing on Einstein’s Special Theory of Relativity and Picasso’s master painting, Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, the play attempts to explain, in a light-hearted way, the similarity of the creative process involved in great leaps of imagination in art and science.” We have not read the play and cannot tell you if Martin is onto anything. But it is interesting to see Martin—and Byrne—ponder how art gets created in the shadow of Heisenberg. Their elliptical notions, though provocative, explain perhaps why the 20th century did not produce artistic greatness.

The Medieval Dowry. In medieval times, Platonic ideas were absorbed and re-invented. Plato, the Greek philosopher who worried about society’s connection to the cosmos, held that there are ideal forms, perfect forms, which we try to recall and emulate in our human pasture. Sundry medievals took that notion in, more or less said that it was true, but put a Biblical slant on it, saying the ideal forms are descended from God and testament to his glory and existence.

What’s pertinent for us in the present age is (a) the idea that there is a perfection for which we should strive (b) that there are ordained forms of truth, goodness, and beauty which comprise perfection and which are inter-related. Perfection is the goal and we don’t have it unless we can bring forward a pastiche of truth and goodness and beauty. None of these values exist without the other. All this is a rejection of uncertainty and a kick in the teeth to relativity.

If Perfection Were in the Wings. In this letter, we have taken the long route around the barn to argue that our hearts and our economy need Plato-like concepts of the ideal. For instance, there is hardly a city in America that one could call beautiful. Perhaps New Orleans. But the rest are at best orderly with occasional touches of handsomeness. We would think that beautiful urban spaces can only come about (and we are increasingly an urban nation) if large swathes of the population have a rich concept of beauty. The idea of the beautiful city does not today inhabit the minds of our elites or our general populace.

More importantly, we have said elsewhere that we can only prevail economically if we move from a mass market economy to a boutique economy. Our products and services cannot become special and achieve a craftsmanlike fineness, unless our general consciousness embraces ideas of the true, the good, and the beautiful. If we are to put beauty at the center of our lives, we will have to believe it exists and then weave it into the tapestry of our existence. Our current store of products not only suffer from design defects, but are, in the end, rather drab. We are faltering because we are without a philosophy.

P.S. David Byrne’s Bicycle Diaries recounts his bike trips around some of the great cities of the world, places where we have all been. He sees things we did not.

P.P.S. A host of resources wrestle with medieval concepts of truth, goodness, and beauty. We would cite, for instance, Rudolph Steiner and The Relationship between Neoplatonic Aesthetics and Early Medieval Music Theory: The Ascent to the One (Part 1). What’s most important is to view their interrelatedness in the medieval scheme of things, which means that different institutions of importance were not divorced from one another. Smokestack thinking, as the consultants like to call it, is particularly a modern disease. It is promising that Bryne, for instance, is conversant with so many disciplines and jumps across boundaries. Acute specialization has the power to turn us into automatons.

P.P.P.S. A new biography of Frederick Law Olmstead, America’s greatest landscape designer, grasps, if you like, the interconnection that he saw between beautiful surroundings and a beautiful society: Here is the pithy comment of Michael Lewis on just this point:

His central insight was that there was an indissoluble unity between landscape and the social and economic order. A humane system of labor, like that encountered in German Texas, produced a humane landscape and ultimately a wealthier one. (He reported that slave labor, because of its inefficiency, was actually costlier than hired labor.) In the process, he learned to look at landscape as a practical, aesthetic and moral object, and he came to believe that an act as innocuous as the laying out of a meadow could have broad social ramifications.

In like manner, we can begin to understand why we cannot have an effective society if we are not surrounded by a context of truth, beauty, and spiritual wisdom.

P.P.P.P.S. One of our interesting neuroscientists David Eagleman loves the power of science but grasps its limits. In the end, he knows we do not know about 95% of the universe, especially when it comes to the big questions. This does not at all mean he turns his back on science. But he would counsel passionate scientists and religious zealots alike to be open to the many, many theories that abound to explain life’s greatest questions. If anything, he would press his fellow scientists to be more inventive about explaining deep puzzles. As a neuroscientist he has done a fair amount of work showing how the brain lags a little behind current events in order to make sense of them. For us current science and current philosophy is not adequate, not inventive enough, to deal with the challenges we must confront.

P.P.P.P.P.S. We wonder if Martin has read Einstein’s verse. Einstein was simply a broader fellow than Picasso.

P.P.P.P.P.P.S. John Keats in Ode to a Grecian Urn opines that "'beauty is truth, truth beauty.” As well, Keats and some of the other Romantics worried whether their poetry was a divine madness, or just plain mad. People of soaring imagination best understand the linkages between all things and pray that they be inspired by great forces and not demonic devices.

P.P.P.P.P.P.P.S. Neil Postman thought we should hearken back to the 18th century and firmly believed that the past can enrich the present. The Western World has some need to reach back to its earliest roots if it is not to go the way of all flesh.

P.P.P.P.P.P.P.P.S. Much earlier Henry Adams, historian and more, had described and agonized over a breakneck America that was energy personified, moving so fast, that it was hard to comprehend and alien to an aristocrat who once thought he had a place in the world. For sure he thought the medieval world had its virtues, not the least of which was its unified society.

Home - About This Site - Contact Us

Copyright 2011 GlobalProvince.com