LETTERS FROM THE GLOBAL PROVINCE

GP 30 September 2009: Maine Retreat: Looking Backward from 2009

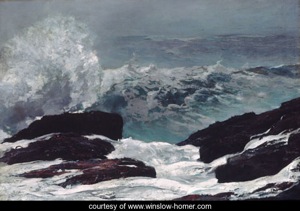

Homeric Maine. Born in Boston in 1836, brought up in Cambridge, a rural burg at the time, Winslow Homer, first an illustrator and then a painter, restlessly prowled both sides of the Atlantic. He had a studio on Tenth Street in New York, wove through the front lines of the Civil War for Harpers Weekly, got to Paris in 1867, worked at his craft on the coast of England in the early 1880s, but found his way to Prout’s Neck in Maine in 1883, effectively his home for the last 30 reclusive years of his life. We think he is Maine’s most distinguished citizen, and his art ultimately tells us what it is all about.

Maine’s a place where thoughtful men and artists retreat, finding comfort in its embrace. The artist Robert Indiana, who also germinated for many, many years in New York City, finally made his way to Maine in 1978. Living across from Rockland in Vinalhaven, Indiana is chatty, as opposed to the tight-lipped Homer. He talks about his art and life at length, and his work visualizes concepts such as Love. The Farnsworth Museum in Rockland, hugely better than your usual regional art space, has caught the loquacious Indiana very well in a current exhibition running through October 25 that also features a biographical movie. Both artists are awfully talented, but the difference in their work explains the transition Maine has made from a taciturn, focused estate where it quietly reckoned with nature and the trials of man to a less salt-of-the-earth society where we are swirling in messages and decorated in words. One paints America; one writes emotive headlines that culminate in media art.

Maine’s a place where thoughtful men and artists retreat, finding comfort in its embrace. The artist Robert Indiana, who also germinated for many, many years in New York City, finally made his way to Maine in 1978. Living across from Rockland in Vinalhaven, Indiana is chatty, as opposed to the tight-lipped Homer. He talks about his art and life at length, and his work visualizes concepts such as Love. The Farnsworth Museum in Rockland, hugely better than your usual regional art space, has caught the loquacious Indiana very well in a current exhibition running through October 25 that also features a biographical movie. Both artists are awfully talented, but the difference in their work explains the transition Maine has made from a taciturn, focused estate where it quietly reckoned with nature and the trials of man to a less salt-of-the-earth society where we are swirling in messages and decorated in words. One paints America; one writes emotive headlines that culminate in media art.

Freshwater. After a short time in Maine, the traveler looks for the miracle of water, even as an escape from the somewhat oppressive,  second-growth timber that covers much of the state. Some choose a lake. But many more beat a trail to the rocky Atlantic Coast which is where Maine’s drama lies and which has figured so prominently in its economy and politics, even if somebody calls it the Pine Tree State. Despite the substantial and varied body of work that preceded his days at Prout’s Neck, we think mostly of Homer’s maritime paintings. More particularly, many focus on later canvases that celebrate the power of the ocean pounding the shore such as in the swirling rush of his Maine Coast shown here. In contrast, Indiana’s disciplined works signal the total control of the artist and assume that man has power over his environment. Homer’s late art hints at forces to which man can only bow. If Longfellow, who came from Maine, can cherish the ‘forest primeval,’ Homer invokes an ocean

second-growth timber that covers much of the state. Some choose a lake. But many more beat a trail to the rocky Atlantic Coast which is where Maine’s drama lies and which has figured so prominently in its economy and politics, even if somebody calls it the Pine Tree State. Despite the substantial and varied body of work that preceded his days at Prout’s Neck, we think mostly of Homer’s maritime paintings. More particularly, many focus on later canvases that celebrate the power of the ocean pounding the shore such as in the swirling rush of his Maine Coast shown here. In contrast, Indiana’s disciplined works signal the total control of the artist and assume that man has power over his environment. Homer’s late art hints at forces to which man can only bow. If Longfellow, who came from Maine, can cherish the ‘forest primeval,’ Homer invokes an ocean that came before man and that will be here after him and that does not really care if man is here or gone. Today that ocean is just as powerful, as we can see in a recent photograph by Peter Kindlmann taken as Hurricane Bill kissed the Maine shore.

that came before man and that will be here after him and that does not really care if man is here or gone. Today that ocean is just as powerful, as we can see in a recent photograph by Peter Kindlmann taken as Hurricane Bill kissed the Maine shore.

Nothing But the Best is Good Enough for Me. Frank Sinatra sings, “Nothing but the best is good enough for me./ I like to eat lobster directly from Maine.” The best in Maine does come from the ocean as it hits the shore, and lobster’s as good as it gets. By and large, it doesn’t taste that great when you get it at some up-market restaurant. Indeed, if eating out, one wants to stop at one of the thriving lobster shacks that hug the Coast where one can taste the freshness. When the fiddling chefs get a hold of it, the taste goes right out of the lobster. It’s better yet if you can cook it yourself, as our colleague testifies on Spicelines.

Lobster prices have dropped through the floor lately, and that has set fisherman against fisherman, with some poaching on one another’s territory, and with the fouling of traps and other vandalism becoming common enough practice. If one listens to real estate promoters or hugs too close to the bustling summer communities on the lower Maine Coast, you may miss Maine’s dark side. It’s tough for many, many to eke out a living, both in fishing and the other skittish trades where natives strive to get by.

Portland’s Food. We’ve put a note up about food in the Mid Coast Region on the Global Province. There’s a slew of new eateries peopled by young chefs that are good, but not as good as their prices would indicate. These cooks, who have often spent time working for noted eateries elsewhere, still need a few lessons, need some more capital to properly appoint their restaurants, and need to learn more artful simplicity and more respect for local ingredients. That’s why none of them cook a lobster you want to eat. The visitor is well placed to find more straight-forward middlebrow restaurants where the owners don’t muck about with the lobster, or the blueberries, or the greens.

Of course, the ingredients can go awry as well. The lobster can take too long to get to the restaurant, even in Maine. Or the blueberries may be grown commercially whereupon the taste never comes alive. Maine produces a big percentage of lowbush blueberries, Michigan being the highbush leader. That said, the berries one finds in the store from either location often are not thrilling, the best this year coming out of New Jersey. Nonetheless, it’s moving to journey up the Coast to Washington County to see the Hispanic-American workers corral the berries. New York photographer David Brooks Stess not only goes up each year to do some picking but also to bear witness to all the labor. Here is his video of the rakers on the barrens. For Maine’s food to soar, one must seek out and connect with very raw, right ingredients, get them to the kitchen with dispatch, and not overlay them with urban civilization’s strange disguises picked up at the Culinary Institute, Johnson and Wales, etc.

Right now second-string cooks up and down the coast are trying to catch up with what’s going on elsewhere, off in the big cities. That’s a hopeless task. Maine, one discovers, never catches up and is always chasing. Better that it find its own voice and not try to be a knockoff. If you’re second to the post, you’re always second.

MaineLines. There are a lot of myths about Maine. Some are fun, tall tales. But some are the stuff of illusion, blinding both visitors and even natives of the state to reality, wreaking certain havoc in local lives smothered by the misguided policies of their leaders. For a long time the North Country Fair’s been pictured as a woodsy place, good for the soul, where body and spirit can come together. In “The Maine That Never Was: The Construction of Popular Myth,” we learn that this idyllic Maine was cooked up by the travel and real estate industries, but it is hardly the stuff of everyday existence:

“This constructed Maine of the publicity bureaus and the railroads is not the same Maine one is likely to hear described by a long-time native of the state--economically one of the poorest in the nation and poorest of the New England States. As characterized by Sanford Phippen, a local Maine writer: "this Maine is frustrating; it is hard on people. It is a life of poverty, solitude, struggle, lowered aspirations, living on the edge." ("The People of Winter" p. 308).

“For the people who live in this state, poverty is the dark side of life. At any given moment, the poverty rate is about 15 percent, according to Joyce Benson, senior planner in the Maine State Planning Office. For rural areas this is closer to 21 percent (Wood 8). But thousands of others are so close to the line that a cutback in work hours or a family illness sends them below, bringing the actual figure for the state to more like one out of every five persons. Thus, the dark woods, deep lakes, crashing surflines and rocky soils of the state are the home of more than 200,000 people whose lives demand a daily struggle to get by. For many of these residents, life in Maine is more apt to be nasty and brutish than it is gentle and restorative of one's soul. And yet this darker image of the state is seldom presented, or even discussed, outside the state itself (although it has recently become a focal theme, or counter-trope, in the writing of new "realist" regional writers of the state, such as Carolyn Chute, who penned The Beans of Egypt, Maine).

“In a word, the realities of "living on the edge" represent a far different Maine from that whose image has been developed and reinforced through at least the past century of mainstream writing about the state-especially by those with major vested interests in luring people with spending money to Maine. The construction and evolution of this image, or myth, of Maine is the subject of this essay.”

We and many of Maine’s own people are maniacs: we have bought into this too rosy-fingered imagery, not seeing things for what they are. Charlie Colgan, professor at the University of Southern Maine, stays on top of the economy as much as anybody. In “Maine Economy: Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow,” he paints the state as in-sync with the rest of the United States, but just a little slow. He sees it struggling to give up its rural background as a supplier of resources to a manufacturing economy in order to become urban and service driven:

“A more realistic view of Maine reveals an economy that is struggling, with mixed success, to make the transition from a low labor-cost, resource-dependent industrial economy concentrated primarily in the rural areas to a high-skill, innovation-driven post-industrial economy centered in urban regions. In making this transition, Maine’s economic future will be determined by a contest between its advantages and disadvantages.”

But we would say its march into services is halting at best. Its new economy is like its cooking--a day late and a dollar short. Moreover, its largest city has less than a 100,000 people and the whole state does not add up to 1½ million people. It is simply not urbanizing or transitioning very fast, and it lacks the scale and density to do so. For Maine to progress, it will have to get past its myths, including its economic illusions, and take a far different course.

Looking Backward. In 1888, Edward Bellamy, a Massachusetts lawyer and writer, published Looking Backward, a Utopian novel that leaps into the future (2000) and outlines all the changes Bellamy thinks would make for the good life. It was a vast bestseller. Naturally his utopia has not come to pass, and it is not altogether clear, as with all utopias, that the future paradise he envisioned was better than the world of his time. There’s a reasonable argument to be made that the future is not all it’s cracked up to be: it may be a loser. Close readers of Aristotle will find out that he did not even think technology, with which we are much in love now, makes for a happier humanity.

Neil Postman, now deceased, but in his day the most provocative professor at NYU, turned Bellamy on end. In Building a Bridge to the 18th Century: How The Past Can Improve Our Future, he makes us suppose that our 20th (and now our 21st) century would be immensely better if it took its marching orders from the 18th. That century was a rich, rich period, not only in the United States, but throughout the Western World. It’s not clear that we always have to look forward to fulfill our destiny. As long as Maine tries to catch up with the United States, it probably will falter. Why not go another way?

Maine’s 19th. Fact is that Maine’s best years were in the 19th when it came into the Union as part of the Missouri Compromise. Its population bursts came from 1790 to 1850, accompanied by relatively rapid development of the economy. As well, that century produced its most nationally renowned politicians, Senator Hamlin who became vice president under Lincoln, James G. Blaine, Speaker of the House and presidential candidate, and Thomas B. Reed, 3-term Speaker of the House, known as Czar Reed. Never in the 20th did Maine achieve a place in the sun equal to its day in the 1800s. Its senators today earn their keep by serving as go-betweens connecting the real power centers outside the state. Maine could do worse than recreate its 19th century in some neo-classical way that still permits it to deal with the 21st.

Certainly this would mean looking to the sea again. Portland, apparently even today, is a bigger port by tonnage than Boston, and a far reaching Portland could once again become a distribution node for Canada, as it once was. A more finely hewn tourist industry—with some standards imposed by the state—could serve as a better magnet for drawing people and investment into Maine. As a starter, Route 1 in Maine, which in some areas is bumper to bumper, would have to be renovated, something the state’s ineffectual politicians have not gotten done. A 19th century restoration in Maine would not so much lead to a services economy, as to a boutique economy with high quality products and services that are distributed far differently than in the mass production world. Smaller boutique enterprises would comport well with the state’s small population. Maine, rather than modeling on the United States, is better served copying some of the smaller nations of Europe which have had to work out a way of living with Great Britain, Germany, and France. States and nations like Maine, at the margin of the map, have to be edge players with a different strategy than those in the thick of it.

Restoration. Maine’s competitive advantage would seem to lie in closing the gap a virtual national economy has put between man and nature, between man and man. In modern complex societies that deal with huge numbers, we’ve become divorced from each other and from the world we live in by computers, and telephones, and corporations, and bureaucracies, and all the other filters that block the arteries. In small, out-of-the-way places we do have an opportunity to restore a more animated and sensory connection to life around us.

In “Where Maine Comes Out of Its Other Shell,” we learn that oysters are coming back to the Damariscotta River region after a hiatus brought on by over fishing and pollution in the 19th and 20th centuries. “These days there are 12 ma-and-pop farms like Glidden Point scattered along the banks of the river.” “Of all the oyster farmers working the Damariscotta, perhaps none here have refined their technique as Ms. Scully has. Before going into the busine ss, she was a marine biologist for 12 years with the state Marine Resources Department.” “Ms. Scully is among the few farmers who still dive for their oysters. She says the technique is less disruptive for the shellfish and ensures superior taste.” “The extra care Ms. Scully takes adds hundreds of hours to the process, but the result is a uniform shell and a buttery, briny taste….” Ms. Scully and her comrades have brought this river back to life—just one illustration of how Maine can build a custom economy by injecting utter quality into simple endeavors. A restoration of greatness.

ss, she was a marine biologist for 12 years with the state Marine Resources Department.” “Ms. Scully is among the few farmers who still dive for their oysters. She says the technique is less disruptive for the shellfish and ensures superior taste.” “The extra care Ms. Scully takes adds hundreds of hours to the process, but the result is a uniform shell and a buttery, briny taste….” Ms. Scully and her comrades have brought this river back to life—just one illustration of how Maine can build a custom economy by injecting utter quality into simple endeavors. A restoration of greatness.

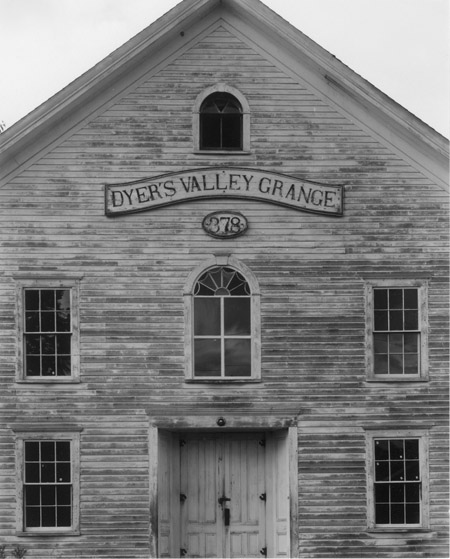

There is a lot of Maine to bring back to life. Erich Hartmann, a magnificent Magnum photographer and a most genteel man, spent his summers in Maine, and could tell wonderful tales of Pemaquid Point, just down the road from Damariscotta. He and his wife Ruth gracefully recorded the Maine they saw, full of beauty, haunted by images of a past that had faded from memory and needed to be dusted off. His Dyer’s Valley Grange, pictured here, amply symbolizes a state that needs to be restored.

Recapturing the Past. On August 28, 2009, Beth Ashley and Rowland Fellows, a forever-young couple in their early 80s, tied the knot aboard the Sea Wife on the Sheepscot River. They had summered in Five Islands, Maine back in 1938. Both had careers and spouses, but finally were widowed and retired. They met up in California where they both lived and found that their memories of each other, which had endured, were true portraits of the delightful people who had summered by the water. So, after a few trips hither and thither, they finally ratified destiny—a life together—70 years later. In Maine one can recapture a past and an America that seems to have slithered away from us in the last quarter of the 20th century. Many of our citizens would like to find that America again. Maine has it in its grasp.

P.S. Maine’s chefs would do well to look to Britain’s Fergus Henderson whose cooking respects the ingredients he puts in his dishes, such that you get the full flavor of his meat—often the organs we set aside in this country—and the vegetables that accompany. He sums all this up in Nose to Tail Eating, which is a devil of a good book. We recently had his lamb and barley stew in which everything was covered with water and allowed to simmer for an hour. Delicious! We’re given to understand that his second book is more elaborate, but less successful.

P.P.S. We never thought Portland’s port amounted to a hill of beans. We did not know, for instance, that it was New England’s largest tonnage port or the largest oil port on the East Coast. For that matter, Portland itself has more of a claim on our attention that one might think. Forbes has voted it America’s most livable city. And the Milken Institute and some others have given it high economic marks along the way. It still seems a little desolate, but that could be conquered with better political leadership.

P.P.P.S. Several 20th century Maine Senators have been distinguished, and occasionally one has been effective. The redoubtable Margaret Chase Smith was America’s first woman senator. Maine today is the only state sporting two woman senators, Olympia Snowe and Susan Collins, moderate Republicans who seem in tune with their constituents in a region that grows ever more Democratic. However, Maine’s success story is George Mitchell who led the Senate and then has gone on to become a distinguished presidential envoy, both in Ireland and in the Middle East. We are hard-pressed, however, to find out what any of these senators have done for their home state. We think this is because Maine lacks a clear idea of what it should do about itself. Snowe, Collins, and Mitchell all have been patient negotiators, good go-betweens, who help gin up compromises between hard-headed legislators and other political leaders.

P.P.P.P.S. “As Maine goes, so goes the Nation.” In the 19th century, and even in the early 20th, Maine was a bellwether. Whichever party won the race for governor in Maine would go on to win the presidency of the United States. But that’s history. Today Maine is on a different wavelength from the rest of us, and it is well for us to understand that it should tack into the wind and go off in another direction.

P.P.P.P.P.S. Portland has a top-notch cookbook shop, one of the best in the United States. Rabelais is very, very comfortable and our colleague has commented at length about it on Spicelines. It's a delight to see publishing people migrating out to the provinces to reap a richer harvest. Judith Jones, book editor for Julia Childs, is off in Vermont raising cattle whose meat will taste like meat, not the pretend stuff you are buying elsewhere.

Home - About This Site - Contact Us

Copyright 2009 GlobalProvince.com