Investor's Digest: Investment Outlook

You are in the Global Province, authored by William Dunk Partners, Inc. You will find additional investment tools and business news elsewhere on this site, particularly in our sections Two Rivers, Agile Companies, Dunk's Dictums, Big Ideas, Best of Class, and Global Sites. Look for more corporation- specific investment advice on our Business Diary page. See also William Dunk's Annual Reports on Annual Reports.

Return

to Investor's Digest Index

August 31, 2011: Investment Outlook 2011: Kick the Tires Real Hard

TV Pundit: What do you think is driving America---ignorance or arrogance?

Titan of Wall Street: I don't know. And I don't care.

The Nifty Fifty. Back in the early 1970's the stock market took a terrible fall. At that time a big, important corporate bank in New York City called Bankers Trust (it is no more) told a young manager who managed its fund of very promising small company stocks that he and it were history. His stocks had plunged, and Bankers decided to focus on big capitalization, hot-performing, well-known stocks like Xerox and Polaroid. In other words, it bought into the Nifty Fifty.

This was a horrible decision. Like Bankers Trust, many of the companies in the so-called Nifty Fifty have since disappeared. None would be called hot numbers today. The young portfolio manager, on the other hand, went on to work for one of the good companies in which he had invested. Later on, we hired him to manage one of the funds we were administering. He achieved spectacular results.

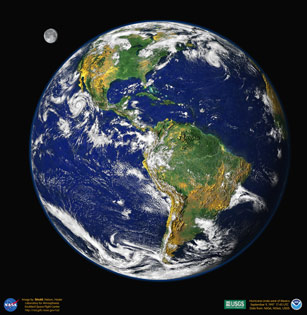

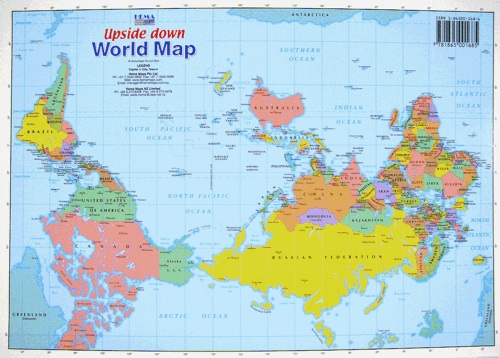

In our 2009 Investment Outlook we cautioned you to look for institutions and companies that are driven by honesty when investing, since it is now such a rare commodity. In 2010 we said you should pursue extraordinarily deep value investments. Now we must remind you of the terrible crash in the 1970's where all the big guys were wrong---full of bad advice and pursuing business policies that would eventually either extinguish or cripple their companies. Amidst terrible global financial and economic dislocation, one must turn one's back on micro thinkers and, metaphysically, take on the globe.

In our 2009 Investment Outlook we cautioned you to look for institutions and companies that are driven by honesty when investing, since it is now such a rare commodity. In 2010 we said you should pursue extraordinarily deep value investments. Now we must remind you of the terrible crash in the 1970's where all the big guys were wrong---full of bad advice and pursuing business policies that would eventually either extinguish or cripple their companies. Amidst terrible global financial and economic dislocation, one must turn one's back on micro thinkers and, metaphysically, take on the globe.

An article in a national journal the other day pointed out that the brokers and institutional salesmen are recommending funds, and bonds, and all the traditional junk put out by Wall Street houses. Yet a goodly number of them have their own money in cash or Treasury bills. They don't know what they're doing investment-wise, but they know they have to sell something to us to make a living. In 2008 Goldman and many of the other prominent houses were selling structured financial vehicles and subprime mortgages, even when they were personally shorting the stuff. In other words, cupidity, arrogance, and ignorance were and are driving financial intermediaries to push financial, air-filled wonder bread not worth pushing. The prudent investor now has to overcome (a) arrogance and (b) ignorance.

Arrogance Aplenty. We're now peppered with humongous companies that are not particularly well-run but grow anyway, because of a lack of real marketplace competition. What a person needs to do is kick the tires one, two, three, or four times and see what happens. Oft as not, the tires will go flat.

The cell phone companies are a simple example of what commonsense will reveal. Before Judge Greene came along and broke up AT&T, America had a benign telephone company that was a pretty well regulated monopoly. Now our telephonic communications are dominated by a small band of very costly freewheeling monopolies. The result is that our mobile phones are poorly built; we have poor national coverage, patchy service with conflicting technical standards, and we pay way too much for all of it. For example, one of our employees found out that it was cheaper to call his home in Indiana from Germany than from the East Coast of the United States. Jerry-rigged and outrageously expensive, these companies are not good long-term investments, since they will have to be rebuilt and regulated in time.

Likewise, the large banks, the major media companies, and an endless list of other goliaths are simply peddling bad products. The lesson of the current continuing financial crisis is to steer clear of companies peddling hollow merchandise. The Harvard Business Review, which is not much of a publication anymore, ran a terribly important article on "Companies and the Customers Who Hate Them" in June 2007. It cuts right to the heart of the matter. In the present volatile business climate, one should not buy the stock, or the advice, or the products of any company one loves to hate. It will not survive, nor will you if you are linked to it. Should you find a company or its wares repugnant, it is undoubtedly arrogant and not a good companion for a humbling age.

Overcoming Ignorance. In good times, investing seemed to be a formulaic business. In the past, some investors would focus on annual growth in earnings, looking perhaps for 15% growth every year. Others would pick oil, others technology startups. In the past any fool might make a nickel, or at least not lose too much. Now such a simplistic outlook will devour one's assets.

We learn that the fellows who are earning a premium today are global macro investors who are following a host of indicators and are darting here and there about the globe with their computers. Brevan Howard, a large macro hedge fund in England, has made $1.5 billion over the last 3 weeks, given its broad-based approach.

We learn that the fellows who are earning a premium today are global macro investors who are following a host of indicators and are darting here and there about the globe with their computers. Brevan Howard, a large macro hedge fund in England, has made $1.5 billion over the last 3 weeks, given its broad-based approach.

A more serious look at the macro fund approach can be had by reading John Cassidy's "Mastering the Machine: How Ray Dalio Built the World's Richest and Strangest Hedge Fund" in the New Yorker.

"Dalio is a "macro" investor, which means that he bets mainly on economic trends, such as changes in exchange rates, inflation, and G.D.P. growth. In search of profitable opportunities, Bridgewater buys and sells more than a hundred different financial instruments around the world—from Japanese bonds to copper futures traded in London to Brazilian currency contracts—which explains why it keeps a close eye on Greece. In 2007, Dalio predicted that the housing-and-lending boom would end badly. Later that year, he warned the Bush Administration that many of the world's largest banks were on the verge of insolvency. In 2008, a disastrous year for many of Bridgewater's rivals, the firm's flagship Pure Alpha fund rose in value by nine and a half per cent after accounting for fees. Last year, the Pure Alpha fund rose forty-five per cent, the highest return of any big hedge fund. This year, it is again doing very well."

It is felt that Bridgewater, Dalio's organization, makes money because of its overseas focus. "Although the firm trades in more than a hundred markets, it is widely believed that the great bulk of its profit comes from two areas in which Dalio is an expert: the bond and currency markets of major industrial countries. Unlike some other hedge funds, Bridgewater has never made much money in the U.S. stock market, an area where Dalio has less experience." Be that as it may, Dalio can be said to make his money by trading the world, a global approach which leads to balance and diversification.

Right now the United States is convulsed by inertia and confused by both ignorance and arrogance. It is a very good time to play global hopscotch if one can learn the rules.

August 4, 2010: Investment Outlook 2010: Life After Death

“Of all the thirty-six alternatives, running away is best.” Chinese Proverb

“The Matrix is a system, Neo. That system is our enemy. But when you're inside, you look around, what do you see? Businessmen, teachers, lawyers, carpenters. The very minds of the people we are trying to save. But until we do, these people are still a part of that system and that makes them our enemy. You have to understand, most of these people are not ready to be unplugged. And many of them are so inured, so hopelessly dependent on the system, that they will fight to protect it.” – Morpheus, The Matri

The World Askew. When the Founding Fathers launched these United States back in 1776, a goodly number of them trucked with Deism. Ben Franklin, George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and even John Adams were thought to have flirted with its precepts. That is, they held that their god had set the natural world, as we know it, in motion, sort of heaving it like a bowling ball from the heavens to the solar system, and then sat back in bemusement to see what mankind would do with it. He was sort of a benevolent, hands-off parent who provided a garden of riches and then patiently waited to see how his children would realize their potential:

Deism became prominent in the 17th and 18th centuries during the Age of Enlightenment, especially in what is now the United Kingdom, France, United States and Ireland, mostly among those raised as Christians who found they could not believe in either a triune God, the divinity of Jesus, miracles, or the inerrancy of scriptures, but who did believe in one god.

Deists typically reject most supernatural events (prophecy, miracles) and tend to assert that God (or "The Supreme Architect") has a plan for the universe that is not altered either by God intervening in the affairs of human life or by suspending the natural laws of the universe. What organized religions see as divine revelation and holy books, most deists see as interpretations made by other humans, rather than as authoritative sources.

For a couple of centuries the nation rocked along pretty well, apparently free of divine intervention, mostly ruled by its citizens’ reason and morality. But in the late 20th century it began to spin out of orbit, and now it is bouncing violently to and fro, with irrationality and fanaticism in the saddle. We anticipated this present state of affairs in our letter “Systems on the Edge of a Nervous Breakdown.” There is virtually no major institution in our society—government, academia, business, church, etc.—that is running well and bettering our society. Gridlock has affected more than Congress and our claustrophobic urban streets: it is the state of the nation. It is not an exaggeration to say that the country created by the Deists in 1776 no longer exists, and a new America must emerge.

Long if not Great Depression. Understanding the apocalyptic state of our world is necessary prologue to any discussion of investment strategy. Our governance and our banks are messy enough that we are forced to buy into the prediction of one economist who says, “We’re in a depression, not a great depression, but one that is bound to go on for a decade. It will drag on.” We would not bring all this up in the dog days of what promises to be an extra-hot August, except that it means that, as investors, we have to get off our duffs today and look for investments in what  have traditionally been all the wrong places. Now is the time to put money where angels fear to tread.

have traditionally been all the wrong places. Now is the time to put money where angels fear to tread.

The immediate causes of our breakdown are a global financial system that is diseased and broken, and a national government that is in paralysis. The Clinton and Bush Administrations totally missed their call to greatness and frittered away great opportunity. Our court system regresses instead of progressing. We know our Congress to be in gridlock. History does tell us we’re in for bad times because we have a government that is unstable and is not governing. Good government is the sine qua non of prosperity.

Only a very few nations have reined in their banks. Most banks, here and abroad, have fallen back into shell games, bad habits, and all the deviousness that netted us 9% unemployment in the first place. Onetime Fed Chairman Greenspan’s pronouncement on the state of our financial mishmash has been widely reported: “Former Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan said the financial crisis was “by far” the worst in history and called the recovery from the global recession “extremely unbalanced.”” We guess he should know since he had a major hand, both inside and outside these United States, in putting us into such financial shambles.

The system needs to be repaired on two fronts. That is, the patent dishonesties have to be rooted out, and financial executives must be threatened with criminal penalties for the most grievous offenses. But, as much, the system is vastly swollen, churning out a host of instruments and transactions that are not needed and creating a bulbous mountain of bogus financial activity. We would hazard a guess that there has been little or no GNP growth in the U.S. for 25 years, if one nets out the financial puffery. In fact, featherbedding in the financial services industry far outweighs and is far more detrimental to our health and welfare than the much talked about padded payrolls of our governments.

The fluff needs to be eliminated so that the resources freed up can be used to build a real economy. No dean of finance has been brave enough to suggest that we need to slice out garbage banking, although ex-Fed Chairman Volcker has at least hinted that most of the financial innovations of the last 40 years have been for naught. We probably will not see the end of our current depression until such time as we have major constitutional reform and we have regeared our banking system, asserting decent government control over it. The recent financial reform bill did not get the job done.

Escape the Thundering Herd. Both individuals and institutional portfolio managers have pretty much invested as they always have, even after the financial chaos in the last stages of the Bush Administration. Those we advise still pray that the volatility will go away, and that life will revert to the ‘old normal.’ The great mass of investors thinks it is business as usual. It ain’t.

Even contrarians who are suppose to bet against current notions and trendy thinking turned out to be rather conventional during this bloodbath. Contrarians tend to go their own way to get some traction until they get a little money in their pockets: then they behave like the rest of us. All sorts of investors did exceptionally well for quite a few years. As a consequence, most everybody followed the herd over the cliff during the 2008 meltdown. Everybody took a 30% hit (or worse) in the last quarter of 2008.

A few parked some cash in the banks. Institutional investors often used Goldman as their depository during the crash, mistakenly considering it a safe, reliable haven. But for the Obama bailout, they would have lost a good portion of their liquid assets.

Meanwhile, even the value of cash has been shrinking. That is, the U.S. currency is suffering a long-term decline in value, as world markets ruminate about the weakness of our economy and our ever- troublesome foreign trade deficits.

The best of the best investors got their skirts muddy, just like the rest of us. David Swensen of Yale, renowned for a spectacular performance for so many years, based on his push into private equity and alternative investments, was locked into stuff that still has not completely recovered, a fate also suffered by the chaps up at Harvard. Swensen, so successful, even wrote a couple of books laying out his wisdom for the rest of us, which was probably a warning sign that he was about to get in trouble. We would suspect, in fact, that his investments were not diverse enough, since he, too, listened to the smart fellows in Wall Street everybody else admires.

Once again, it’s terribly important to pay heed to a chastened Greenspan. This was and is our worse financial crisis ever, and it is not going away soon. It is unprecedented. Now the economists are likening the tremors in our financial markets to earthquakes:

Macroeconomists construct elegant theories to inform their understanding of crises. Econophysicists view markets as far more messy and complex — so much so that the beauty and logic of economic theory is a poor substitute. Drawing on the tools of the natural sciences, they believe that by sorting through an enormous amount of data, they can work backward to find the underlying dynamics of economic earthquakes and figure out how to prepare for the next one.

“If you analyze them, this earthquake law is obeyed perfectly,” notes H. Eugene Stanley, a Boston University physics professor who published a pioneering study of financial markets in the scientific journal Nature. “A big shock causes smaller aftershocks, and then ones smaller and even smaller.”

We suspect, moreover, that the turmoil in our markets is a bit more puzzling than earthquakes. The complexity and chaos theories studied out at the Santa Fe Institute would better explain the phenomena we are encountering.

What 2008 told us and what the present moment tells us is that no investor, small or large, can sit on his hands. There is no safe port in this storm. One has to think very creatively about where to find little oases of value that have escaped mainstream investors and are selling for much less than their intrinsic worth. What one is looking for is deep, deep value that’s unlikely to get wiped out. Often it is value that the accountants cannot put on a company’s balance sheet. It’s time to look for values in unexpected places. Here are some illustrations:

1. Valuable Bankrupts. Early in March 2009, an investor could have bought Wells Fargo Bank for $9-11 a share. Today it’s selling for $27 and change. It’s neither badly run nor well run. As many banks in the tremulous period of 2009, it could have slid into receivership but for the bailout orchestrated by the Obama Administration (and some members of the Bush Administration). It was a buy, not because it had a wonderful, scandal-free balance sheet or huge, wonderful prospects, but because the Government was there to pump it up. In other words, one should look for companies that are hurting or in a stall, but then buy into them because the Government is going to subsidize them.

Chances are that there will be other companies outside the banking and automobile sectors that the Government will underwrite. In other words, one can make a whole lot of bets on Uncle Sam.

2. International Growth. It’s a truism these days that one should look to invest abroad, particularly in Asia. Yet many of the international mutual funds have turned in tepid results at best. Quite often the published accounts for companies in the Far East are questionable, and one can fall flat on one’s face investing there.

Nonetheless, the biggest players know that they have to cross the water. George Soros, the speculator par excellence, has made a great deal of money on currency plays. Warren Buffett, who resolutely tells us all to Buy American, now has put a stream of assorted foreign foodstuffs in his diet. For a while he was a major owner of PetroChina.

But less knowledgeable investors can safely make money with companies that are betting on the poor in poor countries. Such a company is Danone that is selling yogurt, water, and baby food for 10 cents a portion to the impoverished in a host of countries. Formerly it only sold to a narrow band of well-heeled customers in the rich countries: now it is trying for a billion customers by 2012.

C.K. Prahalad, the management guru who instilled the concept of core competencies in us, broadcast a much more valuable idea to us before his death. As we suggested in our 2005 Annual Report on Annual Reports, he told big multinationals that there are many nickels to be made in poor developing countries. Indeed, the major markets of countries in the most developed markets have stalled, and we must pay special attention to the companies that are smart enough to go where the growth is. In this vein, it is truly remarkable that China has become a more important market for General Motors than the United States. There are a significant number of companies that are now coining money in unexpected places.

3. Intellectual Capital. Other companies are sitting on top of unrecognized pots of gold. BioSpecifics is one. It doesn’t make anything. It does not have much in the way of assets. It just owns an idea (patent rights around collagenase) that alleviates skin problems and external irritations that cause a fair amount of suffering. At the beginning of November 2006, one could have bought a share for $2 or so. Today it is just about $24. It has licensed its technology to a partner that is just bringing to market a drug to treat Dupuytren’s Disease.

Look for intellectual capital on the cheap at small companies. R & D at most large companies is slipshod and often unproductive. In fact, our largest drug companies are in crisis, since their product pipelines are so thin.

Samurai Rice. “Every year since 1993, villagers have created pictures by using rice paddies as their canvas and living plants as their paint and brush.” “Last year, more than 170,000 visitors clogged the narrow streets of this quiet community of 8,450 mostly older residents, causing traffic jams and waiting for hours to see the living art.” In Inakadate, Japan, just a couple of weeks ago, onlookers enjoyed “a samurai battling a warrior monk.” Inakadate “has fallen on hard times from a shrinking population, a crushing debt load and declining revenues from agriculture.” It may live again if it can pick the pockets of the many tourists it now draws to its rice paddies.

Samurai Rice. “Every year since 1993, villagers have created pictures by using rice paddies as their canvas and living plants as their paint and brush.” “Last year, more than 170,000 visitors clogged the narrow streets of this quiet community of 8,450 mostly older residents, causing traffic jams and waiting for hours to see the living art.” In Inakadate, Japan, just a couple of weeks ago, onlookers enjoyed “a samurai battling a warrior monk.” Inakadate “has fallen on hard times from a shrinking population, a crushing debt load and declining revenues from agriculture.” It may live again if it can pick the pockets of the many tourists it now draws to its rice paddies.

Villages across Japan are dying, along with the nation’s rice culture. It is fascinating to see fire in the ashes, signs of life where atrophy and sadness seem to rule the day. Here lies both the challenge and opportunity for investors. To find riches where others see nothing but a wasteland. To go where nobody wants to go.

In unusual, hard times, value is created in strange, new ways by people who are up against it. The task for the investor in a world of volatile, straitened circumstances is to be creative enough to root out value that may not be immediately apparent to provincial investors in the world’s financial fortresses who walk with blinders on and run with the herd.

P.S. Agricultural tourism has also taken root in America. Locals here, like the Japanese, have had a hard time figuring out how to cash in on their tourists.

P.P.S. The Bretton Woods Conference in 1944 established a world monetary regime that brought prosperity to the more developed nations of the world, lasting until the 1970s. Since then our global monetary system has been an unsatisfactory patchwork affair.

P.P.P.S. A prudent investor, as opposed to the day trader or speculator, had best know that most of the statistics so ponderously cited by economists and pundits are just plain flawed. One good way to get a fix on things is John Williams’ Shadow Government Statistics. For instance, look at his view of our real GDP.

P.P.P.P.S. Goldman often acts too much like the 2d Bank of the United States which Andrew Jackson had to plough under. It has often confused its public obligations with its personal quest for lucre. Far too many of its ex-officers have been given a role in Government, most dangerously as Secretary of the Treasury. Even the sometimes-reviled J.P.Morgan better defended the nation’s interests than the partners at Goldman. Warren Buffett has lost some of his own golden reputation defending this tarnished institution.

P.P.P.P.P.S. Every serious investor should consider getting the free newsletter, or better yet some of the paid materials, from the folks at BankruptcyData.com. They provide all sorts of interesting information for the informed investor, such as monthly tabulations of corporate bankruptcies. For instance, they spotted “13 public companies file for bankruptcy in July bringing the year-to-date total to 65.”

Company Name |

Bankruptcy Start |

Industry |

Filing Type |

07/30/10 |

Banking & Finance |

11 |

|

07/29/10 |

Energy |

7 |

|

07/27/10 |

Other |

11 |

|

07/23/10 |

Telecommunications |

11 |

|

07/22/10 |

Banking & Finance |

11 |

|

07/19/10 |

Real Estate |

11 |

|

07/18/10 |

Retail |

11 |

|

07/12/10 |

Healthcare & Medical |

11 |

|

07/12/10 |

Hotel & Gaming |

11 |

|

07/09/10 |

Chemical |

11 |

|

07/09/10 |

Heath Care & Medical |

11 |

|

07/02/10 |

Healthcare & Medical |

11 |

|

07/01/10 |

Publishing |

11 |

March 4, 2009: Investment Outlook 2009: The Second Great Depression

Oil in Hell. The tale is told of Harry Svelte, a stockbroker who left this earth before his time, but not because of torrid drinking or blasphemous cholesterol or outrageous womanizing. Not Harry. He was a health nut who had bran for breakfast, yoghurt for lunch, and codfish for supper: his low body mass and ample hair were the envy of the thundering herd at his office. Alas, one day he tripped at the curb, distracted as he was by some ultra volatile market statistics that were flashing in a Merrill Lynch window as he crossed Broadway, only to be run over by an errant taxi cab whose driver was being verbally lashed by a chorine blonde East Side harridan, affectionately called Goldilocks by her 1000 best friends, who was late for liquid lunch with the balding real estate magnate who was keeping her in gemstones. Accidents like that happen in New York City.

Harry was honest enough as it goes and made it to the Pearly Gates for an interview with St. Peter. Rifling through Svelte’s paperwork, St. Pete exclaimed, “Ah, your papers are in order, and you can make it into heaven, even without a green card. But, But—” Peter shifted his eyes, “Look inside. We just don’t have any room. People are simply pouring in, and it is wall to wall.” Harry took off his sunglasses, and, peeking past Peter, he saw that heaven was just chockablock full of people.

He turned away and pondered. He was a clever enough broker. He went up to the gates again, stuck his head through, and shouted, “There’s oil in hell.” Lo and behold, masses and masses of people flooded out. The startled St. Pete then called to him, “Come on in. Now we have plenty of room.” But Harry hesitated and scratched his head.. St. Peter asked, “What’s the matter?” Harry replied, “Well, you see, there might be something in the rumor.” You see, Harry Svelte was a broker.

Devil’s Bargain. Even if there be oil in hell (these days, by the way, the big strikes are coming in from beneath the ocean), we’d advise you to make no pact with the Devil. The Devil, on the surface of things, seems like a jolly enough chap. But, underneath, he may turn out to be Alan Greenspan, Bernard Madoff, Paul Greenwood, Stephen Walsh, James Nicolson, Arthur Nadel, Mark Drier, Allen Stanford, Dick Grasso or one of the thousands of other venal characters who have brought the market low. The Devil has a 1,000 faces.

The conspiracy of dunces and scoundrels who brought our financial system down does not just include a Fed Chairman who threw cash every crisis and did not prick any of the bubbles that led to unruly, inflated markets, nor just hedge fund operators who stole funds, nor just private equity players who stripped companies of assets and leveraged them with debt at Uncle Sam’s expense, nor bankers who made loans that would never get repaid, but also included the brass at every investment banking firm in Wall Street, all of whom knowingly peddled subprime securities and structured debt at the very moment when their firms were going short the very things they were selling. One must understand the pervasiveness of the corruption in financial circles to figure out how to invest going forward.

The way one invests has been turned upside down. You’re foolish if you buy “growth,” or “value,” or certain industrial sectors, or international stocks, etc. The single, over-riding consideration investment-wise is to buy honesty, because it’s a rare commodity, and its value will hold up. If you’re to buy a company, or a government security, or gosh knows what else, you should be looking hard to see if it’s headed by an honest fellow who can look you in the eye and tell you the pluses and minuses. We’re in the hunt for what a Swarthmore psychologist calls ‘practical wisdom,’ which marries shrewdness with virtue.

When Did It All Begin? When did the United States and, consequently, the world financial system, become more rotten than Hamlet’s Denmark? We don’t know, and we are waiting for some academics to take a hard look at this question. We suspect that August 1987 is as good a date as any. That’s when President Ronald Reagan put Greenspan at the head of the Federal Reserve. Ray DeVoe, who writes the most literate and perhaps most incisive letter out of Wall Street, would be as good a fellow as any to ask about when it all began to become a pig in a poke. He’s written convincingly about the successive abuses out of government and Wall Street, including, importantly, the over-statement of our real economic growth rate, and the understatement of our persistent inflation rates.

We are inclined to say the financial system broke free of any governance with the Clinton Administration’s accession to power in 1992, and the deadly sins of omission and commission were compounded during the Bush tenure. Oddly enough, the Sarbane-Oxley Act, which some thought to be a reform of the market’s bad practices, came along in 2002 as one president went off into the sunset, and the other was looking far ahead to the day when he could land on the deck of the USS Abraham Lincoln. As we have said time and time again, it reformed nothing, and was an expensive, deceptive failure, an empty gesture that made the nation feel it had achieved transparency and honest markets. Instead, it was just another sinkhole in our financial quicksand: its main effect was to fill the coffers of accountants and lawyers, the very people who had failed to police public corporations before the act came along. We generous Americans like to reward people who don’t do their jobs: bear witness to all the failed CEOs who have been sent packing with outrageous goodbye sums of money.

The financial system of the United States and of the globe is out of control. We think it fair to say that the mess, for sure, dates back 16 years. And it’s also fair to say that it will take about that long—another 16—to get out of the hole. Chances are that 16 years will be the length of the Second Great Depression. That means that successful, honest market strategists can no longer think tactically and tell us how to play the next market cycle: they should have a 20-year strategy that banks on unstable financial markets. It’s a good time to read the history books in order to understand that things that have been happening for a long time will be happening for a lot longer. And this means that most businessmen, for the first time in their lives, will have to consider becoming strategists, rather than opportunists.

This week the mail brought in a recent investor presentation from the Carlyle Group, a huge private equity firm in Washington that has ties with the Federal Government that make all the lobbyists on K Street look smalltime. Headquartered on Pennsylvania Avenue, it’s a swinger virtually everywhere in the world that counts. Eric Leser in Le Monde once detailed just a few of the well-connected that swam in its sea including “John Major, former British Prime Minister; Fidel Ramos, former Philippines President; Park Tae Joon, former South Korean Prime Minister; Saudi Prince Al-Walid; Colin Powell, the present Secretary of State; James Baker III, former Secretary of State; Caspar Weinberger, former Defense Secretary; Richard Darman, former White House Budget Director; the billionaire George Soros, and even some bin Laden family members. You can add Alice Albright, daughter of Madeleine Albright, former Secretary of State; Arthur Lewitt, former SEC head; William Kennard, former head of the FCC, to this list. Finally, add in the Europeans: Karl Otto Poehl, former Bundesbank president; the now-deceased Henri Martre, who was president of Aerospatiale; and Etienne Davignon, former president of the Belgian Generale Holding Company.”

What the January 2009 presentation says, made simple, is that the country is coming unglued because of ‘deleveraging’—debt repayment or defaults. Bad times will continue for a while, says Carlyle. But then, when balance sheets get cleaned up (by the Federal Government at taxpayer expense, though Carlyle does not care to emphasize this implication), there will be some wonderful investment opportunities. Of course, it is the private equity groups like Carlyle that got us so heavily leveraged in the first place: the hope of the public spirited amongst us is that Uncle Sam will not finance their next follies. It is important, however, to know that the financial gunslingers, like Carlyle, hope to prowl the plains again, and it will take some dexterity to stay out of their sights. Watch out for your wallets and your livelihoods. At the end of the day, probably the other Carlyle has done a lot more for us and American civilization.

Never

Make Predictions. Movie Mogul Sam Goldwyn

akaSchmuel Gelbfisz (and manyothers besides) was reputed to have

opined: “Never make predictions, especially about the

future.” It’s not just that Wall Street is venal: the whole

predictive decision-making process in that swamp is tarnished from

beginning to end and needs serious revamping. In “Formula

for Disaster,” Wired, March 2009, pp.74-77, we learn

that the financialmodels of David X. Li, which the Street bought hook,

line, and sinker, were terribly flawed, and did not expose the risks

lurking just around the corner. The collapse of John Meriwether’s

Long Term Capital Management in 1998 also stemmed from

terrible gaps in risk analysis, with events coming to pass that

ostensibly had one chance in a million of happening. Sooner or

latter, the once in a million always happens. Those who have been

around the track a few times know that risk evaluation is simply

terrible: the schemes and even the staffs of home lenders commonly

accept people for mortgages who should not get them, and as commonly

reject people who are very creditworthy. By and large all the

fancy financial models offered up by the Street and other institutions

just don’t tally risk accurately in the most extreme

circumstances, the very kind of conditions we are experiencing

now. Chaos-and-complexities mathematics that is investigated at

the Santa

Fe Institute comes closer to what we need in our new world where

once-in-a-lifetime events happen every day.

Never

Make Predictions. Movie Mogul Sam Goldwyn

akaSchmuel Gelbfisz (and manyothers besides) was reputed to have

opined: “Never make predictions, especially about the

future.” It’s not just that Wall Street is venal: the whole

predictive decision-making process in that swamp is tarnished from

beginning to end and needs serious revamping. In “Formula

for Disaster,” Wired, March 2009, pp.74-77, we learn

that the financialmodels of David X. Li, which the Street bought hook,

line, and sinker, were terribly flawed, and did not expose the risks

lurking just around the corner. The collapse of John Meriwether’s

Long Term Capital Management in 1998 also stemmed from

terrible gaps in risk analysis, with events coming to pass that

ostensibly had one chance in a million of happening. Sooner or

latter, the once in a million always happens. Those who have been

around the track a few times know that risk evaluation is simply

terrible: the schemes and even the staffs of home lenders commonly

accept people for mortgages who should not get them, and as commonly

reject people who are very creditworthy. By and large all the

fancy financial models offered up by the Street and other institutions

just don’t tally risk accurately in the most extreme

circumstances, the very kind of conditions we are experiencing

now. Chaos-and-complexities mathematics that is investigated at

the Santa

Fe Institute comes closer to what we need in our new world where

once-in-a-lifetime events happen every day.

In fact, the math models, which ultimately are mechanical in nature, just aren’t a match for the forces swirling around in Mother Nature. And the fanciest prediction and risk stuff coming out of the financial community is a disaster waiting to happen. In time, we are likely to look at risk and many of the other imponderables of our society with something more organic that is akin to ‘swarm intelligence,’ the interactive smarts demonstrated by bees that are part of a hive in which the group can find right answers, though any one bee would be at a loss. “Swarm intelligence,” which we have covered in many places on the Global Province, has the potential for addressing risk, terrorism, our healthcare mess, and several other phenomena that are currently overwhelming us. The Wisdom of Crowds, by a New Yorker writer, addresses some of its dimensions. The problem is for us to tap into ‘swarm intelligence,” as opposed to groupthink or herd behavior which so characterizes our financial leaders. Currently we have only made imperfect attempts to imitate swarm intelligence in our human and robot systems.

Where to Park Some Money? About eighteen months ago we began to poll our clients to make sure they either had plenty of cash or were going to sell enough securities to be dripping in it. Many of the smarter big boys were heavily in cash already, sometimes in direct defiance of their investors who wanted to see all the cash ‘put to work.’ The prudent money managers did not let all the loose change burn a hole in their pockets.

But we were not asking them to get invested. Urging them to stay on the sidelines, we wanted to know where they had their cash. Many of the big institutions more or less had their cash parked at Goldman: we said to them, “What makes you thinks Goldman Sachs is safe?” It wasn’t, although Warren Buffett has since given it some expensive capital to keep its feet dry. Kindly note that the Treasury and the New York Stock Exchange have been littered with Goldman types for the last few years: look where that has gotten us.

Parking one’s assets is the big question now. One should not be staying up nights wondering if you’re making money. As Ray DeVoe and others have said, “A whole lot of people have gone broke reaching for yield.” The challenge is to hold on to what one’s got, and that’s not necessarily easy. Many are relying on Federal Deposit Insurance to save them if their bank goes down the drain, but if enough banks go down, one could wind up waiting a fair piece before the payoff arrives.

In “The Great Solvent North,” Theresa Tedesco of Canada’s National Post proudly claims that Canada has a better (regulated) banking system than the United States, and, as a consequence, it has not experienced U.S. style meltdown. We’d debate her at length about how good the system is: we think the Canadian banks have been a long-term drag on the economy and Canadian culture. Nonetheless, its banks are not feeling as much pain at the moment, and it is one of the small economies of the world where for now some of one’s assets can be safer. The investor today must look for benign ports like this, but, further, one must spread the money around, because today’s safe port may be hit by a tornado tomorrow.

Think Small. Inside the United States, but even around the globe, the question is to think small. Pick small countries: we have commented on several small interesting countries on the Global Province. But pick small companies as well. Large companies, not just banks, but GE, or Warren Buffet’s Berkshire Hathaway, are so large that they are part and parcel of the GNP. If the fortunes of the whole country are in trouble, then big GNP companies will tank sooner or later. It is just a matter of time.

For now big companies with subprime or junk merchandise (we are talking about hard goods that you can touch, not financial products) are doing pretty well. Wal-Mart is finally turning in a good performance, buoyed by a bad economy in which consumers have downgraded their tastes and their expectations. McDonald’s is doing well as people on the run gobble down fatburgers. Other bargain chains such as Family Dollar are shining amidst the gloom. Of course, these companies will hit the wall sooner or later, but they’re drawing in consumers during the early part of this severe downturn.

Moreover, there’s another compelling reason not to be investing in large companies with huge stock floats. The institutions—mutual funds and banks and pension funds—invest in them. As the big investors suffer, they will peel off more stocks at fire sale prices. And there are simply not enough buyers out there. One wants to be investing in all the places the big boys won’t go. Safety is now defined as something that CREF, or California’s state pension fund, or the big failing banks won’t touch.

Needless to say, there are small stocks, in sector after sector, that are relatively unscathed, their prices holding up pretty well. Generally institutional investors mimicked the S&P last year, falling somewhere between 30-38%, their performance even worse during the last quarter of 2008. By way of contrast, the portfolios we manage in-house were down 15-17% last year. One fund out in the nether regions which we follow closely proudly said it was only down 5% in 2008: there aren’t many of those. When the professionals start bragging that they did not do as badly as the S&P, then it’s time to invest in some other way. It’s time to jettison the experts.

Jim Rogers. We referred to Jim Rogers, Investment Biker, in our last investment report in 2007. He played a large part in the fabulous early successes of the Hungarian American investor George Soros. Now and again, he goes down some torturous routes: we remember that he began his round-the-world auto adventure in Iceland, and nearly got wiped out there. It was almost a very short global tour.

That said, we think he makes a point or two. He hangs out in the Far East and thinks the world is moving in that direction—particularly towards China. One must figure out some durable ways to invest in Asia in spite of the risks posed by porous financial regulation there. And he’s been enthusiastic about commodities: lately he’s been talking up oil and some agricultural crops. At any rate, he’s broadly telling us to go where others aren’t, and that’s the central theme of this investment perspective.

DIY. Do-It-Yourself investing is quite the fashion in some quarters. Smart citizens realize they won’t lose any more money than the so-called professionals. Oftentimes, they will do better. Here is what one reader has to say:

So what am I doing? Three basic things. First of all, we are keeping any available cash in fully insured places. Secondly, our portfolio is very diverse (a friend told me recently that his “nest egg” was tied into a single bank stock. I have heard that tale too many times.) Third, while I don't pretend to be more than passably competent as an investor, I have never believed in discretionary accounts. Accordingly, Elizabeth and I make whatever investment decisions there are. Only my 201(k) is in mutual funds.

Many professional investors, as we have noted, are immoral, sometimes dumb, often forced by the nature of what they do to invest in things that are doomed to fall to earth. There’s a seasoned journalist in Washington who has followed big investors for years, but has never found a publication which will run the real article about them he thinks he should really write. That is, he believes the only people who make money in Wall Street are the brokers and investment bankers, never the customers. Now, when almost everything is headed downhill, it’s pretty likely that the only one that can save a mom-and-pop investor is mom and pop. Like Ralph Waldo Emerson, it’s time to start believing in Self Reliance.

Jeffrey St. John. Years ago one of our colleagues was interviewed for an hour on the radio by Jeffrey St. John. St. John was a quick study, offbeat and irreverent. Two things always stick in our associate’s head about the conversation. St. John said, “Well, all Wall Street amounts to is Ivy League Socialism, right? Just a bunch of guys who went to well-known colleges who are overpaid for not doing much.” St. John also asked our sidekick, “When you get down to it, the stock market and all that investing stuff is just a roulette game, don’t you think?” The answer was yes. It’s good to remember that Wall Street, and the banks, and the pension funds, and the mutual funds, and the hedge funds—they’re just all a bunch of imperfect ways for losing your money. If they have not made off with it already. (03-04-09)

Investment Outlook: July 24, 2007. We have been baleful even as the market has sailed up. So you might have missed some of the run-up in stocks over the last 2 years if you had listened to us. As it happens, we were better on what sectors to invest in than we were on the direction of the market. We will be revising our opinion more often in the future, but cautioning you just as much. The market madness—both stock and real estate—has resulted from flawed public policy, particularly at the Federal Reserve. Most of the smart grey old men who have made a ton of money from investing are pretty much agreed that we are in for a wicked tumble sometime soon.

We would particularly refer you to John Bogle’s comments in “Bogle Sees Tough Times Ahead for Stock-Market Investors,” Wall Street Journal, March 7, 2007, p. D1. “Here comes Mr. Bogle, warning investors that modest returns may lie ahead”:Mr. Bogle reckons stocks will average 7% a year in the decade ahead. He gets that estimate by dividing the market’s performance into two parts, its investment return and its speculative return.

The investment return is easy to calculate. You simply add the market’s 2% dividend yield to its long-term earnings growth, which might be 6% a year. The market’s performance, however, will likely stray from the resulting 8% return, thanks to changes in price/earnings ratios.

But there has been one change in Mr. Bogle’s advice: He has become keener on international investing, in part because he foresees a weakening of both the dollar and America’s position in the world.

He says investors might allocate up to 20% of their stock-market money to foreign shares, dividing this money equally between developed and emerging markets. But because foreign markets have lately done so well, he suggests moving slowly. “If somebody is at 0% and wants to go to 20%, take two years to do it,” he says.

Warren Buffett, in case you have not noticed it, has also been headed for the border, working his money overseas in all sorts of ways.

Going international is a tricky business, but it’s got to be done. The international mutual funds have often given investors spotty returns. And some of the hottest markets—notably Asian but others as well—lack proper regulatory supervision, and you can easily lose your hat.

Previously we have said that Jimmy Rogers (the investor) seems to be ornery enough to get a lot of things right. He says get out of the U.S. (we are running up a trillion dollars of new foreign debt every 15 months), get into China (it will be the leading economy in the world), and still buy commodities-both oil which is still not in ample supply—and agricultural goods where there are also shortages (too much corn now being used for ethanol). If we are to believe him, you might get out of U.S. stocks and stray into commodities and China.A lot of soft spots in the economy should make us ponder as well. One investment summary concluded: “Recent data indicates that the economy is not performing as strongly as expected. Fourth quarter (2006) GDP growth, initially reported at 3.6%, has been revised downward to 2.5%. This is one of the largest downward adjustments in some time and can be attributed to considerably larger reductions in business inventories than previously forecast. Additional factors were the decline in sales of residential homes, production cutbacks in the auto industry, and a lackluster trend for business investment.” We are troubled as well that businesspeople really lack strategies, improvising on the run. They still don’t sense the very new rules of business imposed by the 21st century. The first quarter 2007 was lackluster, but the second quarter in the United States picked up again, even with all the pain surrounding housing and subprime mortgages.

What investment gurus call the Wall of Worry is mounting throughout the world, not just with wise old men like John Bogle. Hedge fund guru Nicholas Nassim Taleb, whom we discussed in “Irishmen Who Married Up,” believes we are going to encounter unprecedented volatility in our financial markets. “Now, Mr. Taleb has a new book, The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable, a bestseller that follows his Fooled by Randomness, published in 2001, which enjoys a cult-like status in the hedge-fund industry” (Wall Street Journal, July 13, 2007, p. C1). “In it he argues that most investors don’t properly understand the risks they are taking and overlook ways to survive a steep market decline. Many investors plan for rainy days, he says, but not for tornadoes.” As the Journal summarizes, “Hedgie-Cum-Author Returns to the Game;Waiting for a Crash.” In other words, some investors really believe that hurricanes and huge volatility are on the way.

That troubles lie ahead can be seen in the machinations of the private equity funds. With interest rates beginning to firm, the flood of worldwide liquidity on which they depended shows signs of drying up. That being the case, they all seem to be going to the public markets to raise equity, since cheap debt may be evaporating. In effect, they are palming off their bad goods on public investors. When companies go public, we usually think the best returns are coming to an end. In any event, the flood of cash around the world created by irresponsible policies of all the central bank authorities around the globe is disappearing, and the chances of volatility and private equity meltdown are multiplying. So we are hard at work looking for ports in a storm. Often that means finding stocks and bonds and other instruments that the big players regard as too insignificant to merit their attention.

August 17, 2005. House Built on a Weak Foundation. We’ve not issued a new investment outlook since the first quarter of 2004, since the thinking put forth there—to search around in deep value sectors of the equity markets and in some unusual asset classes—has not been too risky a course even amidst the bubblegum economy around the world. But things have now gotten more chancy in mid-2005, and it’s time to be goin’ elsewhere.

Some of you will remember a long forgotten chant, we think from Harry Belafonte, that ran, “A House Built on A Weak Foundation / Cannot Stand / Oh No, Oh No!” The housing boom is beginning to bust. It and all the rest sits on a weak foundation. It had stemmed from worldwide policies that fostered excessive consumption to include easy money. Prescient Wall Street seer Ray DeVoe can now say “I told you so,” since he has been warning us about puffy housing markets for a couple of years. At last the Fed is firmly and consistently ratcheting up interest rates, having previously flooded us with money. This is Alan Greenspan’s last act as Fed Chairman before his presumptive retirement in January: it looks like he is conscience-stricken and abashed at his spendthrift ways, ready to take on the virtuous mantle before he is carried out of office.

Even before his reversal on interest rates,

the housing bubble, the successor to the Internet bubble, was beginning

to quiver in the breeze. Now signs of distress are pouring in,

noticed by all but real-estate promoters, whose venal hope springs

eternal. They’re still building sumptuous, awkward palaces all

through exurbia. If you wander down the street, you may see a new

house a-building that looks much like a dormitory. Squire

Firehock of Staunton Virginia advises us that CNN has provided an ample

list of housing markets, led by Boston and closely followed by several

other East and West coast locations, that are ripe for meltdown

entitled “America’s Riskiest Real Estate.” Seattle, Pittsburgh,

and Indianapolis are still safe harbors. But much of the rest is

over the top (http://money.cnn.com/2005/08/03/real_estate/

buying_selling/pmi_riskiest-markets/index.htm).

Even bleaker

is the data, only some of which has been published, on the mounting

inventory of unsold housing. The Wall Street Journal

(August 12, 2005, pp. A1 and10) notes “Rise in Supply of Homes for Sale

Suggest Market Could Be Cooling.” Houses on the shelf are up

sharply in San Diego, northern Virginia, Massachusetts, Chicago, Las

Vegas, and Orlando (www.nytimes.com/2005/08/13/realestate

/13froth.html).

Swensen’s Doubts. If rising interest rates and declining housing fortunes are not enough to make you nervous about your investments, then take a read of David F. Swensen’s new book Unconventional Success: A Fundamental Approach to Personal Investment. He’s the wizard at Yale who has generated 16.1 percent long term returns, a record other institutional money managers can only dream about. This has been instrumental in giving the university an endowment in excess of $15 billion as well as a $500 million-plus annual contribution to its operating budget. He’s an interesting fellow who beefed up the portion of Yale’s portfolio in equity and alternative investments. We have had calls from more than one chief executive asking how to copy the Swensen approach.

He had set out in his book to show the individual investor how to copy his approach. But he has since realized that Joe Doaks simply can’t do it. Poor Joe does not have Yale’s research. He can’t access great hedge managers. All the mutual funds skewer him, overcharging for mediocre or worse performance. So dour Swensen would basically have us invest in a mix of index funds where one can at least avoid excess transaction charges.

Don’t take Swensen too seriously. But take him seriously. Like all experts, he has fallen into the trap of believing in experts and expert methodology. Be assured, for instance, that we and our associates, without benefit of inside information, superior research expertise, or Street wizardry, have long exceeded the averages. So you can, maybe, do better than Swensen thinks you can.

But his book, coming out now, has great

symbolic value at this very time. It’s a warning to us. We

are now in financial quicksand where it will be easy to lose your

shirt, for the world financial markets are truly a mess: they’re in

much worse shape than when we published our last report in early

2004. Things are so bad that you truly can expect horrendous

returns, if you are looking for short term results (i.e., less than 7

years). Don’t buy for tomorrow or the day after tomorrow; even

the hedge funds are now having trouble investing for 2-, 3-, or 5-year

cycles. Look out a decade. Read about his book at www.nytimes.com/2005/

08/13/business/13nocera.html

and see Swensen at

http://mba.yale.edu/faculty/others/

swensen.shtml.

The Bernstein Index. Peter L. Bernstein is a marvelously literate investment advisor and one-time OSS operative, Air Force captain, college teacher, and researcher at the New York Fed (www.peterlbernsteininc.com). For the individual investor, he’s a more important read than Swensen because he has a wider compass. In 1996, he came out with Against the Gods: The Remarkable Story of Risk just as we were entering a world where risk management skills became more critical in running the nation, the economy, and one’s portfolio. Risk assessment surely would have kept more of us out of some of those Internet stocks that crashed and burned, and would contain some of the awesome hubris that still afflicts us in this new century. In 2000 came his Power of Gold, just as it became more and more profitable to plough a bit of your lucre into all sorts of commodities.

Now, equally timely, is his Wedding of the Waters: The Erie Canal and the Making of a Great Nation. By implication, it tells us and the nation where to invest now. (See www.foreignaffairs.org/20050301fabook84235/peter-l-bernstein/wedding-of-the-waters-the-erie-canal-and-the-making-of-a-great-nation.html, www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/articles/A54777-2005Jan6.htmlm.) This is the story of the building of the Erie Canal—linking the Midwest and the East to Europe and the world through New York State. Its 300-plus miles made New York the Empire State, and New York City the capital of the world. Interestingly, it was New York politics and finance that put the canal together, just as it will be developments initiated at the state, instead of federal level, which will account for America’s future greatness in the world. New York State is sorely in need of another De Witt Clinton—a man who had enough push and vision to realize New York’s Manifest Destiny at the Canal’s opening in October 1825.

See our “Courtly Congressman, Amory Houghton, Jr.,” where we contend that even today New York State can play a unique role in rebuilding the national infrastructure.

Now we must each find out own Erie Canal to back. The risks today are too big to manage; commodities and alternate investments, even oil, may turn down quite a bit by 2008, and so one’s investments must drift into areas that will mature some time well over the horizon. Running around in present day markets, busily turning over your portfolio to look for gain or to avoid risk, is probably a zero-sum game that will run down your assets. The wise Bernstein cautions you not to press too hard:

The day-trader phenomenon would not have developed out of a population that was thoughtful about how the stock market works. And I don’t think that many individual investors have learned that the more you press, the more problems you’re going to get into. They have not learned that, and maybe they never will. A lot of investors feel it isn’t hard, they just don't know how. After 50 years I still haven’t got it all clear. And that’s okay, because I understand that I haven’t got it figured out. In a hundred years, I won’t have it all figured out (http://money.cnn.com/2004/10/11/markets/benstein_bonus_0411/m).

In the present environment where there is no safe house: you had best not scurry about like a trapped rat but, instead, find a way to settle down for a while out of the turmoil.

Infrastructure. As we have mentioned in previous letters, there is almost no aspect of our national infrastructure that is not worn out. Moreover, what we have is engineered for yesterday and is in no way suited to the challenges ahead. For instance, our electric power grid was built in a time when our power plants were near the people who would use the electricity. Now we transport power over long distances which means we need a system with national controls, standards, and technology that looks much different from the grid we have today. We will have more blackouts, not just because we have under-invested in our electric power structure, but also because our concepts and policies have not kept pace with the realities of our marketplace. In every way, we need to rebuild the foundation of our country so as to provide underpinnings for our society and to secure our national destiny. What then are some examples of “infrastructure”-type things where investors can take a long-term plunge?

Alternate Energy. Most of the captains of industry and policy wizards in Washington claim that alternate sources of energy outside of oil and nuclear fission can only provide a drop in the bucket of our power needs. That said, as we have said in several places in Big Ideas, alternate energy is beginning to make a difference and some of it is even becoming cost competitive with fossil fuel. See our entries on “Shale,” “Oil, Oil, Everywhere?,” “Fusion Time,” “Manure Power,” “Solar Power Revisited,” “Running on Empty,” “Water Batteries,” “Blackout 2003 Equals Blindness 1990,” “Power and Water,” “Wind Power,” and “Ocean Power.”

In general, General Electric is a substantial play in alternate energy if you want exposure to wind, solar, and other types of energy development. See “GE and Alternate Energy.” The trouble here, of course, is that you are buying into all sorts of businesses, not just alternate energy, when you invest in General Electric.

Windpower alone may be a more interesting

investment where you can find interesting companies solely focused on

whirling blades. Wind energy is slowly becoming rather cost

competitive with fossil fuels, and many countries are making

commitments to it, from China to tiny Denmark. Denmark, in fact,

now derives 15% or so of its energy from the wind. For a good

introduction to wind energy and its possibilities, see

www.windustry.com/basics/01-introduction.htm. Perhaps the

world’s leading windpower company is Vestas (www.vestas.com/uk/Home/index.asp),

which supplies turbines to power companies around the globe. It

has had some financial bumps but has an outstanding market position.

Its homebase is, incidentally, Denmark, the very nation that has

made such a deep commitment to windpower. Though the U.S. showed

early enthusiasm for windpower, as it has for many new technologies,

its engineering was weak; the Europeans have since overcome some of our

design flaws (www.economist.com/displaystory.cfm?story_id=3850262).

The hopeful outlook for wind energy in the United States is summed up

at www.economist.com/

displaystory.cfm?story_id=526754.

Windpower is a very good

example of how one should invest in future ideas: pick a future niche

where the economic model and profit potential are almost right today.

Even if the affluent around Cape Cod are stridently resisting

windpower in their backyard, we are going to have a whole lot of it

(see

“Tilting at Windmills”).

We still consider sunpower to be a speculative arena. We have, nonetheless, listed a host of providers on the Global Province and find it interesting that Germany and Japan have make more progress in solar development than the United States. Despite the fact that the cost per kilowatt is still tres cher, the demand for solar panels has suddenly bolted upwards, and manufacturers currently have not been able to keep up with demand from contractors.

Education and Knowledge Transfer. It’s clear that we are becoming dumber, and that our schools at all levels, both private and public, are failing to equip Americans with enough smarts to play the value-added, knowledge intensive role that lies at the heart of its increasingly service-based economy. Just as women in Arab states such as Saudi Arabia are eroding the chains that hold them down simply by becoming better educated, education and knowledge are America’s hope of not becoming a vassal of Greater Asia.

Slowly, very slowly, private business is learning how to make a dent in this sector. Various outfits, from Michael Milken’s Knowledge Universe, to the Edison Project, to Sylvan Systems paved the way with experiments that had limited success, Sylvan probably having the most impact (www.educate-inc.com/aboutus.html). All have tried to supply add-ons to America’s public education colossus, though some commentators perhaps would feel they merely offered band aids for a fatally flawed system.

Probably the key to revamping everything and reaching isolated, backward areas of America is online education. This is dependent on the growth of cheaper access via municipal wireless. A host of companies are committed to making a dent in virtual education, none more so that Pearson in Great Britain. There an American, one Marjorie Scardino from Texarkana, has come in, cleaned out the ragtag of businesses that made up the Pearson portfolio, and focused it both on publishing and, more particularly education. Along the line, for instance, she picked up Prentice Hall’s powerful set of entries in educational publishing. (See www.economist.com/displaystory.cfm?story_id=372400, www.pearsoned.co.uk/Aboutus, and www.pearson.com.) She is pushing more deeply into online education and seems to be reaping better financial results from her determined foray into education.

An even more interesting conversion of a media company into an educational moneymaker is the Washington Post (www.washpostco.com). Its website does not make clear just how far it has gone in education: for the first time, if we remember rightly, education has become the biggest contributor of revenues. In any event, education revenues increased 35% in 2004 to $1,134.9 million. The annual report, by the way, no longer features articles by and about its journalists and its flagship operation the Washington Post, which is now being overshadowed by its Kaplan education unit. As we have said elsewhere (see the “The New Regional Daily”) there has been a challenge for newspapers everywhere to radically redefine their businesses and become very much broader content providers. It would not be an exaggeration to claim that its education business will be the salvation of this company.

There are interesting opportunities aplenty in both training and the knowledge transfer business which are both strongly related to education. As for the latter, we find that companies still do not have a successful dynamic model for archiving, re-using, and sharing knowledge and experiences so as to stoke their own innovation but also to resell intellectual property to others. In general all the companies we have talked about above are burdened with concepts and other baggage from traditional publishing and education which inhibit their potential. Many would be advised to form joint ventures that could provide knowledge management services for several companies.

We have long followed a stripling of a company in Boise, Idaho which has stumbled, bit by bit, into a rather different model. We have previously written about PCS in our Agile Companies section. Sprung out of a computer-repair business, it put up bricks and mortar schools where parents could supplement regular education with extra courses in math, science, etc. Now all the buildings are gone. It has migrated totally to the Internet. Using Internet modules combined with Lego Blocks to give the education a tangible feel, it has been selling its services overseas to developing countries such as Egypt and Pakistan. Gradually it is introducing an entirely different global educational model that even the poor in distant lands can afford (http://edventures.com/index.html). Virtual education, however, is as applicable in developed societies such as ours, where we clearly are no longer getting a bang for our educational buck. Obviously, however, it cannot replace social learning that only can transpire face to face.

Collaboration. Global markets in a

post-Cold War world also have changed the shape of all economic and

governmental activity. No one nation, even the U.S., controls

enough resources, people, knowledge, etc. to implement a global

strategy, and there is almost nothing we can now do of any meaning that

is not both global and complex in nature. In a world where we

lack enough control to get the job done, we must compulsively cooperate

to move the chess pieces around the board. Actors inside and

outside our borders have to play a role in devising a new car, putting

together a defense against terrorism, halting the spread of diseases

that know no boundary, and so on. As Peter Drucker has noted,

strategic alliances and joint ventures are now vastly more important

for forward-looking businesses than old-fashioned, wasteful

mergers. See

http://www.conference-board.org/pdf_free/

annualessay1999.pdf.

Now, as he says, “the real boom has been in alliances of all

kinds….” The problem is for business managers and investors alike

to take advantage of this unprecedented trend.

A host of software schemes, such as Tacit Knowledge and Croquet, have sprung up to foster cross pollination inside companies and around the world. The predecessor to the Internet was devised by DARPA, mostly to promote scientific collaboration. Sundry tools to integrate research on various problems have resulted in undertakings in both open source software and biotech research. (See “Linux for Biotech”.)

We are still a long ways off from the kind

of collaboration we require to move on the biggest problems of the

world. In many ways, conquering space and time is not a technical

problem, but more of a psychological or ethical problem.

Independent, competitive people have to learn to meld their

activities with others, putting aside their go-it-alone proclivities.

Business schools, companies, and others are now pushing courses

to achieve the necessary re-treading of their managers, but only have

made a start (www.economist.com/business/global

executive/displaystory.cfm?story_id=1097093).

For more on the

environment that promotes collaboration, see

www.economist.com/business/globalexecutive/displaystory.cfm?

story_id=417029.

As best we know, the best tangible efforts to achieve collaboration are happening in unlikely areas. In the bureaucratic, sclerotic world of healthcare, for instance, there is a movement called “shared decision making” where coaches try to ensure that patients are extra-informed about their illnesses so that they, along with healthcare experts, can participate in their treatment, shaping the plan for dealing with their heart condition or diabetes. Amongst public companies, American Healthways (www.americanhealthways.com) comes to mind, it having made some efforts to engage patients in their course of treatment. Health Dialog, a fast growing private company which we follow closely, is more formally invested in all the disciplines necessary to achieve patient collaboration. It is heavily focused on making patients aware of the full range of clinically reputable treatments for their condition, and it drives each patient to accept responsibility for acting intelligently with the surfeit of information at hand. See our details on Health Dialog at www.globalprovince.com/healthdialog.htm. In fact, Health Dialog is fond of referring to its process as collaborative care (www.collaborativecare.net).

As interesting to us is another private company called Virtual Agility, which provides a software dashboard for controlling giant collaborative endeavors that cut across time zones and a host of independent participants (www.virtualagility.com). Its first applications involve very independent-minded government agencies that must attempt massive coordination on various questions of national security. Interestingly it provides a tool that all sorts of people can agree to use.

Probably the most advanced forms of collaboration now occur in the supply chain management process. Wal-Mart, for instance, has built its low-cost, low-quality discount model on superior logistics based on digital replenishment and systematic information exchange with its suppliers. Land’s End, now part of Sears, Roebuck, has built a made-to-order jeans system, allowing you to input your measurements and quickly get your pants back from factories in Central America or Malaysia: we waxed enthusiastic about “Land’s End Made-to-Order”, but now, of course, Land’s End is a rounding error in the Sears/K-Mart behemoth, and we wonder if it can have much impact on the Company’s management process.

Even in supply chain logistics, most of the interesting companies are private and not accessible to public investors. For instance, Harry Lee’s TAL Apparel in Hong Kong (see “The Shirt King”) is doing everything from design to replenishment on shirts it is producing for a host of branded retailers in the United States, and it is reputed now to be pushing into underwear. Clearly it has a more collaborative relationship with its customers than the Wal-Mart model allows, since the confrontational folks in Arkansas are noted for pushing their suppliers to the wall. TAL Apparel is beginning to achieve the kind of collaborative effort that current business practices do not normally permit.

Today the public investor wanting to get a foot in collaborative waters will probably buy a stock like Amazon, which is using its internet marketing machine to peddle a host of products it does not stock. This has stoked its revenues and profit performance, while adding significant volume to some of the third party merchants who sell through its website. In days to come, companies imbued with a much richer collaborative ethic will come to market and offer significant value to investors who can hold out to 2015. Investments in collaborators are hard to come by, but this is where the big money is going to be made.

March 24, 2004. Andrew Smithers, an economist and consultant in London, claims that one of the biggest mistakes investors make … is failing to accept that there are often no good investments available. (See the New York Times, March 21, 2004, p. BU 7). We accept his wisdom, but then say, “So now what do I do?” In times of risk, look for security in the most dangerous places. Like the rest of the investor pack, we have turned ever more wary. Stocks—and the investment portfolios of even the smartest managers—have been moving sideways since the beginning of the year. We believe U.S. equity markets are vastly overpriced, fueled as they are by a flood of money from the Fed, coupled with tax policies that encourage rampant speculation. The job picture is still lousy, prices at the gas pump are soaring, and turmoil has invaded the political affairs of every major country. We no longer expect spectacular returns from deep-value, unnoticed, low-capitalization stocks.

Just to prove that we, too, have a herd mentality, we, like many others, are suggesting alternate assets, but, in fact, it’s hard to move in and out of the quirky asset classes that offer clear value. Suddenly, we realize, it’s hard to find another place to park your money. It’s even tough to be in cash, since currency is taking a kick as well. So where do you go?

In risky times, paradoxically, the safest places to go probably are areas that are taken to be broken and dangerous, away from the herd. For instance, our energy and healthcare systems are a mess. You learned this last summer when your lights went out, or at the hospital when the surgeons inserted a stent that did not do you any good. So we are suggesting oil and energy (the Middle East will continue to be roiled, and the Saudis will have to cut production to maintain their sway in Middle East affairs) and health, pharmaceuticals, and medical devices (our population is getting older and sicker faster in a healthcare system that believes in crisis care instead of prevention). Some narrowly defined, niche companies can capitalize on the unstable conditions in these industry areas. For the adventurous, there is a nickel to be made overseas, investing in a few uptick countries out of the mainstream, such as Malaysia, which has just re-elected the government party over irksome Islamists, that are looking perky lately. Finally, there are still several dollars to be harvested in takeover plays: We should see more of these now that the investment bankers are staffing up again. What you’re looking for are pockets of affluence and stability in disturbed industries and a volatile world.

September 10, 2003. Hubris being what it is, we are probably headed for a fall. Below we correctly said you should put 15% of your monies in a short fund, 60% in high-quality small-cap stocks with very low valuations, and 25% in new asset classes. As of 8/29/03, the NASDAQ composite was up a whopping 39.14% for the year. You could have even done better in some of the small-cap stocks we were talking about. These are good companies that are low-priced because major institutions cannot be bothered with them, and because they’re often boring manufacturing companies that don’t excite the young turks of investing. In fact, we would say you could continue to pursue exactly the same strategy for a while longer and do pretty well.